Feeding the Body Politic: British Satire in An Age of Revolution

As TU seeks designation as a high research activity institution, TU Magazine will each issue bring readers a story of high-impact research. This edition we spoke with art history professor Nancy Siegel about exploring American history through the depiction of foods in 18th- and 19th-century popular culture.

Abstract—Siegel’s research into political satire, identities erased from food history, American botany and culinary activism will culminate in an international exhibition titled Curious Tastes and the book “Political Appetites: Revolution, Taste, and Culinary Activism in the Early American Republic.” The research discussed here is her examination of politically charged recipes and how satirical prints using food iconography exposed consumption and corruption in the British Empire ahead of the American Revolution. There is a related, multi-part documentary tentatively scheduled for 2025–26 to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

A Conversation With Nancy Siegel

Q: Your last project was about 19th-century American landscape painting. What changed your focus?

A: For a lot of academics, we find our next great project in footnotes. While finishing a book on Thomas Cole, considered the father of the Hudson River School of painting, I was looking at a piece of British pottery that featured one of his prints. I wondered, “What would somebody eat out of this?” It was the same time the French government decided not to support American troops in Iraq in 2003. And a member of Congress decided that french fries must be called freedom fries in federal cafeterias. This was such a strange notion, but I wondered: Is there a connection between politics, food and visual culture?

A teapot decorated to celebrate the repeal of an unpopular tax.

“Bostonians paying the excise man or tarring and feathering (1774),” a print attributed to artist Phillip Dawes.

An image of a recipe for Republican Cake contained in the Colchester Cookbook dated September 1813.

The cover of “American Cookery,” written by Amelia Simmons in 1796, which is the first cookbook written in the new United States.

Q: Why was food used to make a point in the satirical prints?

A: Imagine a cartoon depicting King George III placing a fleet of ships in an oven to be baked like gingerbread. Visual metaphors like this linked political figures and events to food and commodities, forming the basis for a distinct genre of 18th- and early 19th-century satirical prints made by British artists sympathetic to American colonists during the Revolution. The culinary iconography in these prints spoke to the conditions and events that ultimately dismantled the British Empire: non-importation movements in the American colonies, food riots in London and the surrounding countryside, complex trade embargoes, protests over taxation and revolution.

Q: How were women involved in political action through food?

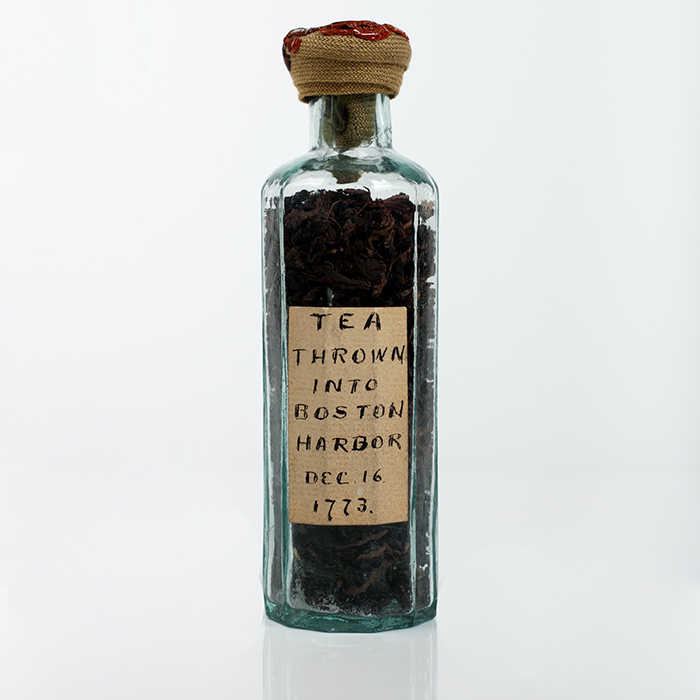

A: Prior to the American Revolution, non-importation movements—in which colonists refused to drink imported tea or wear imported cloth—became a way for women, in particular, to become politically active. For example, at the Boston Tea Party, members of the Sons of Liberty wore stereotyped costumes of Indigenous people to hide their identities, but in the next year in Edenton, North Carolina, 51 women signed a pact not to drink imported tea. They sent their petition to George III and they didn’t cover up their identities. Their actions were lampooned in a widely disseminated engraving depicting women as foregoing their motherly duties and adopting the stance of men. Likewise, I have hundreds of recipes for things like Election Cake, Washington Pie and Franklin Buns. Developing such recipes were ways in which women became participants in the democratic process. Because they couldn’t vote. They couldn’t own property. So they took to the kitchen and created these incredible recipes.

Q: How do you share your research with the public?

A: I travel around the world conducting historical cooking demonstrations and lecturing. I’m always in the kitchen making some new recipe—trying to truss a hare according to an 18th-century direction or refining a recipe for Federal Cake. Two years ago, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut had an exhibition focused on the Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton duel. I recreated that duel in culinary form. It was Federal Cake versus Republican Cake. We voted with nutmegs, because Connecticut is the Nutmeg State, to see who would win the duel this time. It was fun, but it also made a poignant point about these recipes that were developed by women to demonstrate an awareness of political structures.

Q: Why were satirical prints such an effective means of political criticism?

A: Artists such as James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson legitimized public opinion and increased demand for prints in which formidable figures were called to task. Through inexpensive etchings and engravings produced and sold in London then exported to New York and Philadelphia, these depictions criticized the underlying consumption and corruption in British trade and commerce. These engravers were the Stephen Colbert of their day. While today we laugh at the way monologues mock politicians and current events, satirical prints are the 18th-century version.

Q: Have you had trouble finding primary sources?

A: No, just the opposite. I have spent many hours over the last decade going through thousands of handwritten recipe books by women, where they also made notations. They took the time to write these recipes down, so they were important. The fact I can find recipes for Washington Pie for decades means it had this very long shelf life. Those are magical moments because the women’s recipes and letters are so incredibly intimate. I see these books almost as a diary. They’re very personal. Sometimes they have intergenerational inscriptions so you can see mothers handed these down to daughters and then to their daughters. They were, and continue to be, valued.

Q: Were the politics of the time reflected in the ingredients women used?

A: In 1796, Amelia Simmons writes “American Cookery,” the first cookbook written in the United States. She used ingredients like pumpkin and corn—foods co-opted and termed American. This is an important moment because it eliminated the Indigenous identity associated with these foodstuffs. Some of the work I do focuses on a conversation about how we define the American diet. We owe so much to the peoples who were marginalized. And now is really the time to bring them into the forefront of this conversation.