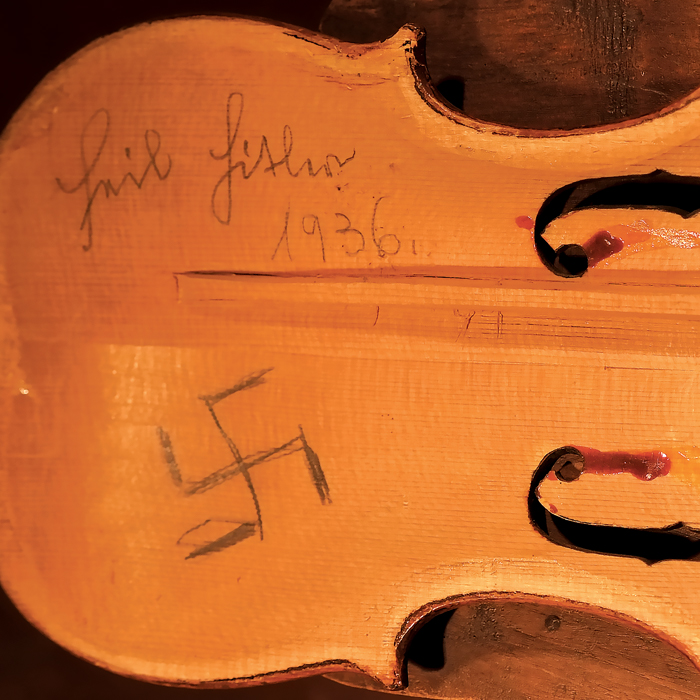

Heil Hitler Violin

A few years ago this instrument was purchased by a violin maker in Washington, D.C., who discovered the inscription.

The symphony Jonathan Leshnoff wrote for the Violins of Hope honored both their past and present.

The silence was stark.

Five seconds elapsed. Then 10 ... 20 ... 30 more. The audience sat transfixed, trying to comprehend the emotion of the moment.

It wasn’t just the beauty of TU music professor Jonathan Leshnoff’s Symphony No. 4 that so enchanted the crowd. Nor was it the dazzling precision and skill with which the members of the world-class orchestra played the piece.

“It was almost as if we knew we were in the presence of history,” says Giancarlo Guerrero, who conducted the Nashville Symphony that night in March 2018.

Thirty-six of the string instruments on stage had never been played during a performance by the musicians who cradled them. But these were not shiny new violins or priceless Stradivariuses.

They are survivors.

The Violins of Hope is a collection of restored instruments that once were played by Jewish musicians during the Holocaust. Over the course of the past 75 years, each found its way from concentration camps, pogroms and other horrifying circumstances to one family’s music shop in Israel, where they were meticulously restored. Now that family shares them with the world.

“The way we see it, the only way to prevent something like that from happening again is through education,” says Avshalom Weinstein, whose grandfather started acquiring the instruments around 1945. “Unfortunately, we have less and less survivors. Time takes its toll. Those instruments are testimony. They were there.”

It was for these—not any—violins that Leshnoff specifically composed “Heichalos,” a work inspired by an ancient Jewish mystic text. Although he finished the symphony at the end of 2017, he had not heard it performed for an audience until he sat in the concert hall that spring night in Tennessee.

“It felt like everyone was there for a purpose,” Leshnoff says. “I saw all types of people coming together for something positive and to make a stand on what history was and where it should go.”

Perhaps those in the audience took some time to consider where the instruments had come from, or who had previously played them, after Guerrero lowered his baton. Maybe some people simply were moved by Leshnoff’s composition, or the orchestra’s passion and precision. Whatever the case, men, women, and children sat in a kind of rapture for nearly a minute until, as if snapped from a trance, they burst into applause.

One of Leshnoff’s earliest memories from his childhood in New Jersey is of his parents giving him a box of crayons. He used them not to scribble, but as drumsticks.

“When I was three or so my parents played Beethoven’s fifth on an LP,” he says. “When the music started I felt a current of energy. I remember standing there stunned. Beethoven has been my favorite composer from that day on.”

He began putting notes on paper around the age of 10 but didn’t get serious about it until high school, during which he also played the violin. When he was accepted to the renowned Peabody Institute in Baltimore, it was for composition.

Leshnoff, now 46, joined TU’s faculty in 2001. Four years later he published his first symphony.

“The best way to start the symphony is just having something to say,” he says. “When I am asked to write a concerto for a solo instrument with the orchestra as an accompaniment, my voice has to go through the violin. I have to think about my ideas and say them through the violin. But when I write a symphony I can be myself. I’m writing for every instrument without any one taking priority.”

Composing can be an isolating, laborious process. Leshnoff works in his office on the second floor of the Center for the Arts, first sketching his ideas by hand onto score drafts. Last year, he entrusted 78 linear feet of manuscripts—everything he’s written from the time he was a kid through his four symphonies—to TU’s Special Collections and University Archives.

Next, he uses an electronic piano and keyboard to enter notes into his computer. When he needs to hear an actual piano, he sits at one in a classroom across the hall.

Leshnoff’s works have been performed by more than 65 orchestras worldwide in hundreds of concerts. He has received commissions from Carnegie Hall, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the symphony orchestras of Atlanta, Dallas, Kansas City and Pittsburgh.

Listen to some of Leshnoff's symphony No. 4 for the Violins of Hope.

“We had already decided that we were going to do a CD of his guitar concerto, which he had written for the Baltimore Symphony a few years before, and we had already decided to record ‘Starburst,’ which is an overture he had done a few years back,” says Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony music director and six-time Grammy winner. “This Violins of Hope project came up and we immediately thought of Jonathan. To me his writing for strings has always been quite fascinating—he’s a really gifted orchestrator. It was one of those right moment at the right time.”

At first, Leshnoff, who is Jewish, admits that he felt pressure writing for a specific set of instruments that had, as he puts it, “witnessed death.”

“I was awestruck for many months thinking, ‘What are you going to do?’” he says. “Ultimately I have to take responsibility for every note in the piece. I’m carrying a message of triumph, of hope, of social justice, of history, giving voice to the voiceless. It had a tremendous amount of weight on my heart.”

For inspiration, he turned to “Heichalos,” an ancient book written in Biblical Hebrew.

“My music for the past five, six, seven years has focused on putting Jewish mystical spirituality to sound,” he says. “With this symphony I went one step further. Instead of just having a movement, I dedicated the whole symphony to an ancient mystical text that is 2,000 years old. It’s essentially a meditative guide.”

He describes the first movement as a “frightening” scenario. While it can be jarring, it’s upbeat and includes the full orchestra—woodwinds, horns, percussion and all. The second movement features the strings.

“I wanted to unite this text with the instruments themselves,” he says. “I see the instruments as the physical embodiment of Jewish survival. These instruments must have witnessed thousands of people killed, and here they are. Just as I’m here, as my relatives escaped Europe. Not only was I writing for these violins, feeling their pain, but I was trying to unite the intellectual with the physical.”

When Guerrero first heard the symphony, he deemed the piece unmistakably Leshnoff’s.

“When you make a commission, you never know where the composer is going to go,” he says. “When we did the first run through in the first rehearsal, we could hear Jonathan’s signature language in the music. For many composers that’s impossible to find, but the ones that do are incredibly successful. It was obvious to us that he put his heart and soul—who he is as a composer and a person—into this music.”

The horrors of the Holocaust sometimes had a soundtrack. When the Violins of Hope came to Cleveland in 2015, PBS ran a story about the project. During the opening of the segment, a Holocaust survivor recounted his arrival on a cattle car of a train at the Mauthausen Concentration Camp in 1944.

“There was a huge gate with the name on top and the term ‘arbeit macht frei,’ meaning, ‘work will make you free,’” the man says. “As we entered, there’s an orchestra playing Beethoven. It was an unbelievable sight. People were being killed and beaten and there’s an orchestra playing.”

In Israel, after the war, no one wanted to touch anything German, according to Avshalom Weinstein. Yet his grandfather began purchasing instruments that had survived the Holocaust and storing them in his workshop. Beginning in 1991, Avshalom and his father, Amnon, began restoring them.

“We repaired cracks, pegs, sound posts, varnish, we reset strings,” Avshalom says. “Some of them were played outside in the rain and the snow. We did huge work on each one of them.”

They now have 77 beautiful instruments, each with a name and a story. The Auschwitz Violin was originally owned by an unnamed inmate who performed in the men’s orchestra at the concentration camp—and survived. The Heil Hitler Violin is presumed to have been owned by a Jewish musician or amateur who, at some point, needed a minor repair job. The craftsman doing the repairs opened the violin and inscribed on its upper deck the words ‘Heil Hitler, 1936,’ alongside a swastika. He then closed the violin case and handed it back to the owner, who played it for years, unaware of the inscription.

Steven Brosvik, COO of the Nashville Symphony, became aware of the Violins of Hope when they were in Cleveland. He immediately knew he wanted to bring them to Music City. Over the course of 10 weeks in 2018, 26 community organizations throughout the city used the violins to create both musical and non-musical educational content.

“Musicians who played these instruments were forced to play during executions,” he says. “They played basically as a ruse for people coming off the trains to give them a sense of comfort. The instruments were used as tools of deception. Certainly here in Nashville, where it is such a music community, the concept that people would use instruments in that way is pretty striking.”

That was plainly evident when the members of the orchestra first assembled to select their instruments and rehearse days before the March 2018 concerts. Asking a musician at this level to use a different instrument for a concert or recording is akin to telling Serena Williams to switch tennis racquets before the Wimbledon final. Like chefs and their knives, a musician’s instrument is not merely a tool—it’s an extension of their being.

Kristi Seehafer, a section first violinist, described selecting her violin as a “cerebral” process.

“Each instrument has its own feel and response and sound,” she says. “Reaction times of the strings, where the strings are in relation to the fingerboard. All of that was so very different. Knowing that I had to play it for a concert was a little bit scary because I couldn’t quite make it do what I was capable of on my own instrument. At the same time, I recognized the importance of playing these instruments. Given the history of the instruments and what they represented, I felt it was really important that we give them a voice.”

That voice obviously resonated with the people in the recital hall, and it can be heard clearly on the CD of Leshnoff’s work that the Nashville Symphony released on May 2, the United States’ annual commemoration of the Holocaust. It was the first time the Violins of Hope had been recorded on an album.

“Usually when we talk about the Holocaust we talk about numbers,” Avshalom Weinstein says. “But these sounds, the joy these instruments produce, cannot be quantified.”