Faces of the Frontline

Words by Megan Bradshaw

Film photography by Lauren Castellana ’13

We asked alumni and faculty in a variety of health care disciplines to share the challenges they’ve faced during the pandemic. What they told us was both heartbreaking and hopeful.

Evidence-based treatments. Compassion. Anatomy and physiology. Flexibility. Health assessment and diagnosis. Empathy. College of Health Professions students start working in health care facilities before graduation, learning all the skills—hard and soft—they’ll need to provide high-quality care for the rest of their careers. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, those skills were urgently needed. Nearly 75 nursing students graduated early throughout 2020 to aid Maryland’s fight against the novel coronavirus, joining thousands of TU alumni already in the trenches.

These are their stories.

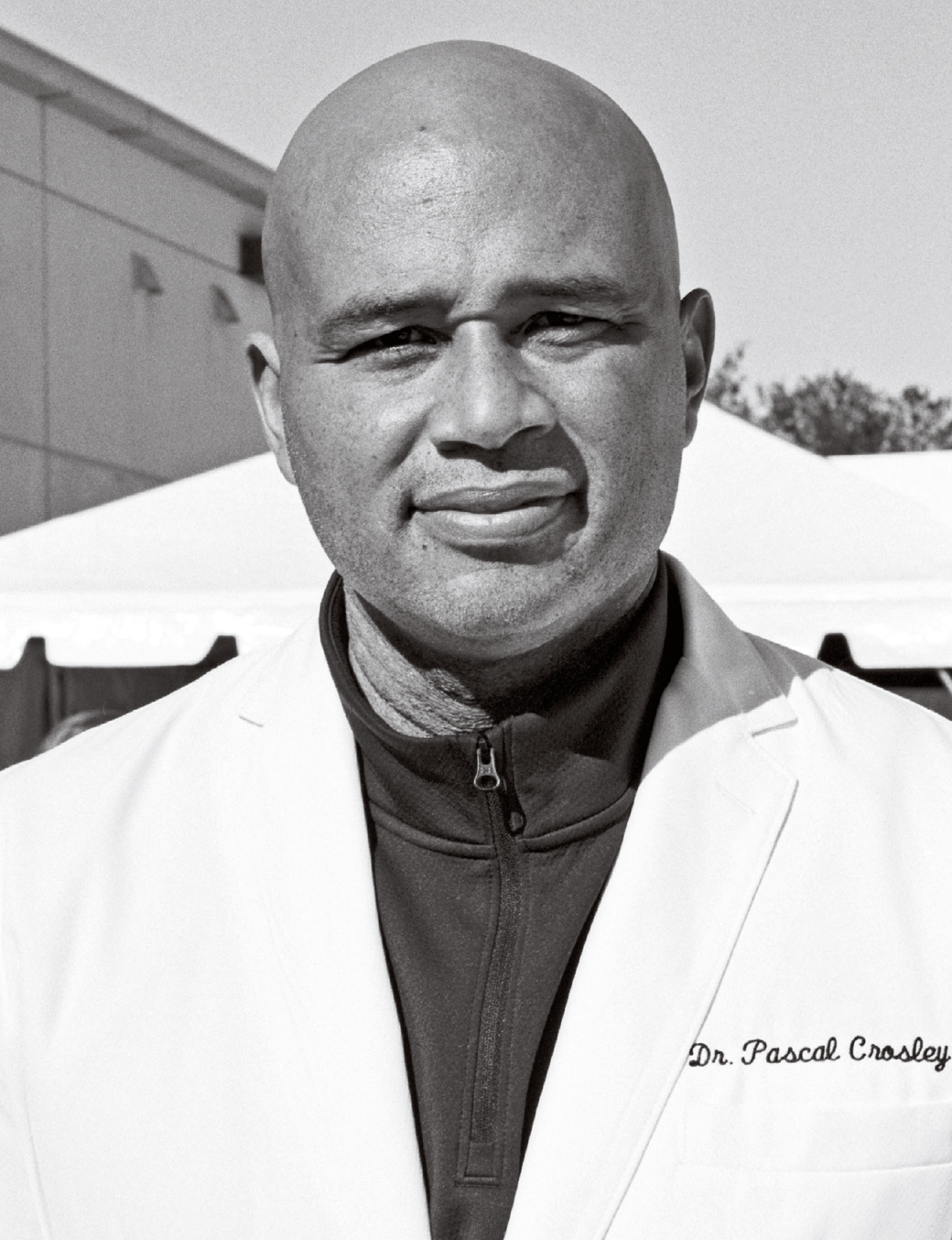

Pascal Crosley, M.D.

Owner, Quality First Urgent Care

Class of 1993

When I opened my urgent care in Howard County in December 2019, I hired advanced providers, physicians’ assistants and nurse practitioners to work with me. We provided a good level of care and were building links with the Burtonsville community.

Then the pandemic hit. There were a lot of unknowns, a lot of fear. Because I was an emergency doctor, I was comfortable with PPE and isolation rooms and able to stay open.

I developed a drive-through testing center in the back of my urgent care. A lot of frontline workers were becoming very sick, and they were showing up pretty regularly with symptoms of COVID.

The testing grew from 50 a day, 60 a day, 70 a day, and on and on, until I developed more efficient processes and then opened two more testing centers at the Savage and Elkridge volunteer fire departments. The most tests I’ve done in a day is 2,000.

Once we got to Thanksgiving, at the peak of the fall surge, I’d have 115 cars in line at each of my testing sites.

The resulting traffic meant we needed to develop a walk-up process. In the back of our urgent care, I have a respiratory center with a 65-foot tent and fresh air pumping in. I take care of respiratory and COVID patients and COVID testing in that particular part of the urgent care.

It was evident to me early that testing was going to help us get out of this. Keeping people safe, delivering medical care—especially in an area that I grew up and lived in—is what I’m most proud of.

Tim Ames

Physical therapy assistant, GBMC

Acute Rehab Unit

Class of 2016, 2020

Before the pandemic, you didn’t have to worry about getting your temperature checked or wearing a mask when you came to work. Now, you get a little sticker—a different color every day—to let the patients know you’re symptom free. I work with patients to get them up and moving. You don’t want them to stay in bed all day; otherwise, they develop things like pneumonia, bed sores or blood pressure imbalance.

If the patient is positive, you have to treat whatever brought them into the hospital—stroke, abdominal surgery—and COVID. With COVID patients, you really need to get them out of bed to increase their breathing as much as possible.

When you go into the room, you wear a gown, N95 mask and face shield. Two or three months into the pandemic, it became normal. “OK, I got my walker, the face mask and the N95. Now I’ve got the equipment I need to treat patients.”

A good thing we have done is having iPads to talk to family members and bring a little bit of joy to patients while they are sitting in the hospital. One of the hardest parts is the patients can’t have their family visit. It’s hard to explain to them. Some understand. Others don’t.

Another hard thing is hearing about a patient you've been working with, that’s been close to you, who has suddenly passed away. That’s the toughest day at the hospital. You work with a person. You’re doing your best. The person is getting up every day, walking the halls. The virus just takes a toll on people differently.

But one of the best things is seeing a patient who has progressed from being in an intensive care unit to going home and back to an independent lifestyle. That’s the best feeling ever.

Kathleen Resnick

Administrative coordinator, GBMC / volunteer firefighter and EMT

Class of 1994, 2000

My background is adult ICU and ER. When the pandemic started, not being at the bedside was hard for me because I want to be there to help people.

When you see multiple members of the same family dying within the hospital, it’s difficult. When you have a husband and a wife who both die. Their children have COVID, and they can’t do a funeral. It’s difficult. It’s not a hoax. That’s why we need masks and to wash our hands and social distance. People don’t realize how quick it can spread.

As a firefighter with and president of the Pikesville Volunteer Fire Company, I’m proud that we take the same precautions as we do at GBMC. Everyone has to have full PPE and N95 if they’re within 6 feet of a patient. If they’re not, they have to have a mask on at all times inside the building.

Service is truly my life. My neighbor’s house caught on fire a few months ago, and my husband and I were able to run down and help them before our equipment with our gear could arrive.

All the members of my fire company are strong people. I think we were prepared for something like this. Even though we didn’t think it would happen, I think we knew, in an emergency, we can do it, whether at the hospital or at the firehouse. Being a Towson grad, I feel like the nursing program and the professors we had gave us what we needed for success.

Rodnita King Davis

Nursing educator and registered nurse,

Notre Dame of Maryland University / York Hospital

Class of 2012

For the past five years, until mid-summer of last year, I was working at York Hospital in the post-anesthesia caregiving room. We recognize there are potential hazards to the job. But you almost feel like you can control those to a certain extent. Then, when the pandemic hit, it felt like this extreme loss of control. There were so many unknowns and quite a bit of fear.

I had a spray bottle of Clorox in my car. I was spraying down the soles of my shoes before I put my foot in the car. I had a trash bag draped over my seat. When I got in the garage, I was stripping down, flipping my clothes inside out and carrying them straight to the washing machine and turning it on as hot as the water will go, pouring whatever sanitizing solution I had available.

Now at Notre Dame, we’ve reduced room capacities and mandated that students wear masks and face shields. In my health assessment class, I keep them at a distance as much as possible, but when you’re doing assessment, typically, you may not put on gloves to just look at someone’s fingernails. But now I tell them, “Please put on gloves for everything.”

When we started classes on Zoom, it wasn’t so much of a problem for me, because strategies I used in the classroom lent themselves to using a breakout room. I always try to see the silver lining and think about things that really work well and some things that we can improve upon.

I’m proud that I’ve been able to connect with some of my peers and show them some of the technologies, some of the things that I’ve had success with doing and really share in that way. I’m also proud that I’ve been able to still connect with my students even though we are physically distant.

We recognize there are potential hazards to the job. But you almost feel like you can control those to a certain extent. Then, when the pandemic hit, it felt like this extreme loss of control.

Briana Snyder

Registered nurse, Sheppard Pratt Hospital

Inpatient Trauma Disorders Unit

TU faculty

I teach full-time at Towson, and I’m per diem at Sheppard Pratt. So I pick up four or five eight-hour shifts per month at the hospital.

I work on the inpatient trauma disorders unit. We treat adults who have experienced very severe maltreatment, usually abuse and neglect, sexual, physical, emotional, verbal—often starting at a very young age and lasting into adulthood. They have diagnoses like dissociative disorders, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, PTSD—related to their trauma.

Things were pretty routine in the psych world, pre-pandemic. Now, it’s difficult to think what’s the same.

The unit is designed to promote interaction, and we have had to totally shut that down. There’s a lot more isolation and loneliness. It’s a shame, because part of the benefit of being in a psych facility is being in that therapeutic milieu where you can interact with other people with similar life experiences and diagnoses and get support from them. That’s a big part of their treatment, and that’s been cut off. During the pandemic, the rates of substance use, domestic violence, child abuse and suicide have gone up. That’s just for the general population. For people with pre-existing mental health issues, it’s gotten much worse.

We in the psych world expect to see the effects of this for months or years. We already have waiting lists for our units.

But, with this pandemic affecting everybody in the general population, I think it’s come to more attention how important mental health is and how quickly it can be affected. People who formerly considered themselves mentally healthy have maybe experienced things that they’ve never experienced in their lives. And I think it’s given folks a new appreciation for mental health care and folks who work in mental health care and the work that we do.

Luukia Morin

Registered nurse, University of Maryland

Medical Center, OB Care Unit

Class of 2017

Before the pandemic, UMMC had a high-acuity, pretty busy labor and delivery unit. We have a lot of complex cases. People come in and things happen quickly, and we’re right by their side.

The pandemic really changed the way that we triage patients. They come in, and we don’t know their COVID status. We all have our N95s with us all the time; we don our PPE every time we go into the room.

I think the biggest change was how many unknowns there were, because we didn’t know how this virus was going to impact pregnant women and their babies. At the beginning we kept asking, “How are we going to do this so that they’re safe, especially for our COVID-positive moms?”

We got really, really sick patients who were intubated and in the ICU, but they were still pregnant and they still needed the fetal monitoring. We had to change the flow of our unit entirely—where a nurse is going to be assigned, off and on our unit.

Even if the mom’s COVID positive, the baby’s not necessarily, so we’re doing a lot of education for moms on wearing their masks even while they’re holding their baby. Which is really sad, not kissing your baby without your mask on if you’re COVID positive. You can breastfeed, but you’re washing your hands and keeping your mask on, and if you have your mask off, keeping your baby 6 feet away from you.

But what I am most proud of is the quality, evidence-based care that we still provide our patients. Nurses are exhausted, doctors are exhausted, but we show up every day and keep giving the compassionate care people need and deserve, even though it feels impossible sometimes.