All About Arete

TU’s new football coach plans to craft a program that will embody the Greek word for excellence.

By Mike Unger

About a month after becoming just the fifth head coach in the more than half-century

history of TU football, Pete Shinnick is sitting in his corner office in the field

house at Johnny Unitas® Stadium. The walls are still mostly bare; since being hired

on Dec. 11, his time has been monopolized by recruiting, not interior decorating.

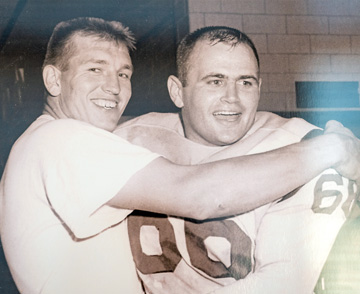

Still, he did make sure a few things were hung. Behind glass in one frame is a photo of his father, former Baltimore Colts linebacker Don Shinnick, squaring up, his form perfect, preparing to tackle an about-to-be-in-pain New York Giant. In another, his dad and Johnny U himself are embracing, all smiles, after a victory (pictured). The elder Shinnick and the legendary Colts quarterback were great friends, and the fact that Don’s son is now coaching in the stadium named for Unitas, well, some people might call that fate.

But kismet alone is not responsible for bringing Pete Shinnick to this place, at this moment. That was accomplished through years of hard work, often as far from the spotlight as a football coach can be. Shinnick has built a resume that speaks for itself. He won at Azusa Pacific, a small California school that at the time competed in the NAIA (roughly equivalent to the NCAA’s Division III). He won at Division II UNC Pembroke, which didn’t even have a program before he arrived. And after starting yet another program from scratch at the University of West Florida in 2014, he won the Division II national title in 2019. In 20 years as a collegiate head coach, he’s amassed a 159-67 record.

Now, a new challenge awaits. Shinnick, 57, has never coached at the Division I Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) level, just one step removed from the top. It was the chance to do that in a place he’s long felt ties to that attracted him to the job.

“When I look at this university and what’s taken place over the course of the last 10 years, you see a growing, vibrant campus,” he says. “Not many FCS programs are in this type of setting. I don’t care who you are, it’s very difficult to get to a national championship game, and so to do it in the D-III level, the D-II level and FCS [as TU has done], that’s unique. Yeah, those are years apart, but it shows that everything aligns and there’s an opportunity for something here.”

Pete Shinnick was born in Baltimore, and though he only lived there for the first five years of his life, his parents always considered it home.

“I think if my dad hadn’t gone into coaching, my family would still be living here,” he says. “My dad passed away about 20 years ago, and my mom still says this is the favorite place that she’s lived. For all the moving that they did, that’s a heck of a comment.”

The Shinnicks followed the nomadic path of a football coach’s family. As Don jumped from one assistant coaching job to the next, first with the Chicago Bears, then the Oakland Raiders, followed by the St. Louis Cardinals, his family moved too. Despite the constant upheaval, Pete loved being the son of an NFL player and coach. Once, he attended a practice in Oakland where he played catch with Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler.

“There was a kid at school who had gotten Stabler’s autograph at some signing session,” Shinnick recalls. “He was showing it to the kids, and I really wasn’t that interested. He was like, ‘What’s wrong, you don’t want to see it?’ I said, ‘Well, I was playing catch with him the other day.’”

Shinnick loved football, but he didn’t start playing until high school. An offensive lineman, he got just one Division I offer, so he took it and enrolled at the University of Colorado.

In Boulder, he struggled to get on the field until he learned to long snap. He knew he wasn’t going pro, so coaching was always in the back of his mind. After an ill-fated marketing internship, the business major was surer than ever that coaching was where his future lay.

His first job was as a volunteer assistant at the University of Richmond. His bank account was light, he worked long hours—he absolutely loved it.

“I enjoyed the competitiveness and camaraderie of it,” he says. “That’s really what has kept me in the game. It’s the most unique sport out there. There are 105 guys. You’ve got a staff. How do you get everyone on the same page? I saw that as a unique challenge.”

As his career progressed, Shinnick made his way to bigger programs. He worked with the defensive line at Arkansas and served as the recruiting coordinator at Oregon State. In between he coached tight ends at Clemson, where he met his wife, Traci, at a Fellowship of Christian Athletes dinner. They’ve been married for 31 years and have four children and two grandchildren.

At each stop, he channeled the coaching lessons he learned from his father.

“His philosophy was trying to make the experience for the player great,” Shinnick says. “The first thing my dad did very well was he never forgot what it was like to be a player. He never forgot that we’ve got helmets and shoulder pads on, it’s hot out here, it’s muggy, there’s humidity. Number two was to really coach the whole person. This guy is under my care, and it’s not just about football. It’s about what type of person he’s going to become, what type of husband he’s going to become, what type of father he’s going to become.”

In 1999, Shinnick was hired as head coach of Azusa Pacific University. Although it’s located just 15 miles west of the Rose Bowl, one of college football’s shrines, it couldn’t be further from the upper echelons of the sport. That first year, his only full-time assistant was his defensive coordinator.

“You can make wherever you’re at be whatever you want it to be,” he says. “What you learn is that you can probably do way more than you thought you could. I learned that the administrative aspect of it is something I’m very good at. Mapping it all out.”

After seven years there, Shinnick moved east to start the program at UNC Pembroke, in rural North Carolina. Success came quickly. In his second season, the team went 9-1. Overall, six of his seven years were winning ones, but he had an itch to face stiffer competition. So it was off to Pensacola, where the University of West Florida was looking for someone to build its program, slated to join the powerful Gulf South Conference, from scratch.

“We started with a phone and a cubicle,” says UWF Athletic Director Dave Scott. “As soon as we hit the ground running with Pete, we knew that he was the right guy because of how he interacted with our faculty and our staff. Pete’s a great communicator. He’s a great motivator. He’s about lifting up the student-athletes, training them to be better people. We want them to be not only successful on the field but in the classroom and in the community. His personal vision matched up well with what we want to do as a department.”

Once again, year two proved to be a breakthrough. The Argonauts notched 11 victories. Two years later, they won 13, the last of which was the national championship game.

From the onset, Shinnick set out to build a specific culture at UWF. Argonauts are a band of heroes in Greek mythology, so for his program’s theme, Shinnick chose the Greek word arete, which means excellence.

“It’s an amazing word to encompass every aspect of someone’s life, to say, ‘Let’s get you to be the best version of yourself that we possibly can,’” says the folksy, affable-yet-driven Shinnick. “We say, ‘Are you living up to your fullest potential when you’re going to study hall, when you’re going to class, when you’re in the weight room, on the practice field, when you’re home as a son?’ I told myself, ‘We’re going to use it here, but if I go somewhere else that’s going to be the standard: Live up to your fullest potential.’”

When TU put together a magical run to the 2013 FCS championship game, Shinnick began taking notice.

“I’ve been tracking their success, and I think there’s a handful of FCS jobs that are unique, that have the combination of location and campus that I would say, ‘Hey, if that ever opened up, that would be appealing to me.’”

The feeling was mutual. When UWF reached the national semifinals last season, TU Director of Athletics Steve Eigenbrot took notice.

“This job had an amazing candidate pool, which allowed us to be very selective,” he

said in announcing Shinnick’s hire. “Ultimately, character and fit for Towson drove

us to this place. We listened to a lot of alumni, fans and supporters. They wanted

someone who understands how to build and run a program and has a history of meaningful

and relevant success.

Obviously, the ability to develop players and recruit were high on the list, especially

with this area being so rich in talent. Pete checked all those boxes and then some.”

After signing a five-year contract, he started working on the roster immediately, convincing leading tackler Mason Woods to withdraw from the transfer portal. About 80 players attended his first team meeting.

“When we talked to our guys it was really, ‘Look, this is who we are and this is how

we do things,’” he says. “’This is the standard that we’re going to hold you accountable

to. If you can grasp all of that, then you’re going to have a great opportunity to

be successful here. If you want different rules for yourself, if you want to fall

into your own category, this is not the

program for you.’”

Shinnick called plays for 23 years, but here he’s relinquishing those duties to offensive coordinator Brian Sheppard. He wants his focus to be more program-wide.

“I think we have a great football alumni group,” he says. “I feel like engaging with them will bring them back into the fold a little bit. I think there’s other things in the community that my time can be spent doing while not having to worry about a practice script or a gameplan in the detail that it takes to call the plays. You still gotta worry about all those things as a head coach but not to the finite detail that it takes.”

Clearly, an abundance of free time is a luxury Shinnick does not possess. As he sits in his office, he takes a moment to reflect on the circular path his life has taken.

“Dad would say what a small world that this has worked out to be,” Shinnick says. “He’d be proud.”

Somewhere, Don Shinnick and his buddy Johnny U are smiling.