The Sky Was Her Limit

There has been much media attention paid to how Marisa Harris ’17 died, but precious little to how she lived.

By Mike Unger

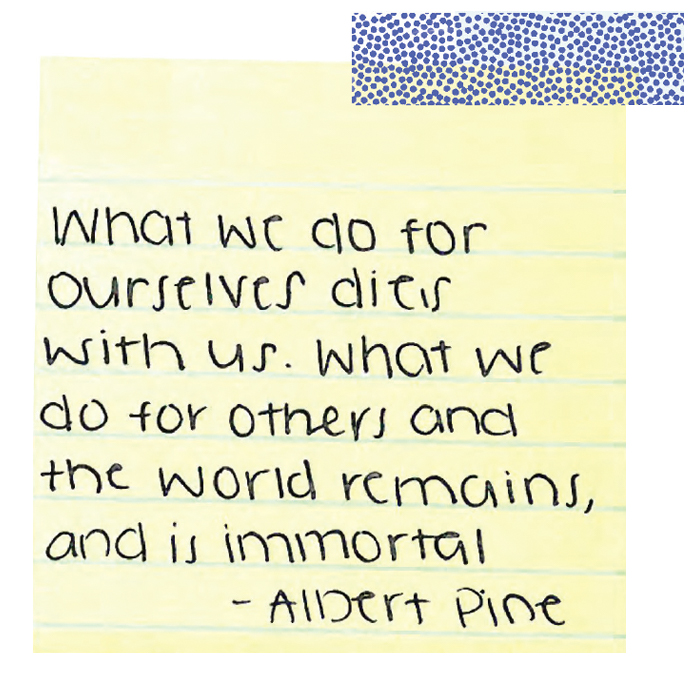

Marisa Harris found comfort in writing her favorite inspirational quotes on Post-it Notes, then covering her desk with the yellow, green and blue stickies. She began this ritual in middle school, which hinted at her intellectual maturity, and wrote her last one in college, by which time it was apparent for all to see.

Her mother, Leigh, has a fondness for the one to the right, which she says captures the spirit with which her daughter navigated the world.

“Although I can say with 100 percent confidence that Marisa had no sense that her life would be cut short, many of the quotes she transcribed reflected an urgency to live each day to the fullest, to help others in need, to be a good person, and speak to a legacy Marisa may have wanted for herself, whether knowingly or unknowingly,” she says.

Just 22 years old when she was killed in what her parents call an incident, rather than an accident, Harris’ short journey had already led to love, happiness, and a clear calling. Alternately outgoing and reserved, silly and serious, daring and practical, Harris ’17 graduated summa cum laude from TU with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. She’d known exactly what she wanted to do professionally since she spent her sophomore spring break in Mexico — not partying in Cancun, but working with the kids of single mothers and victims of domestic violence at a free daycare program in San Miguel de Allende.

The trip was a game changer for Harris, who knew little Spanish yet traveled by herself for the first time to get to the city in the far eastern Mexican state of Guanajuato.

“This experience, although short in time, stuck out from all the rest,” she wrote in a personal essay she submitted with her graduate school application. “I learned a lot about multiculturalism in the helping field, as well as the importance of understanding that a person who needs help is not inherently helpless. My time there also solidified my interest in specifically working with children.”

From her earliest days she’d always treasured her time with kids, no matter whether they reciprocated her affection. At TU she worked with children both as a neurobehavioral outpatient intern at the Kennedy Krieger Institute and in the burn unit at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Sometimes, the kids would pull her hair or even spit on her, yet when she returned home she’d talk for hours about the empathy she felt for them and her desire to help them improve their lives.

Harris was in graduate school at Marymount University pursuing a master’s in clinical mental health counseling when she and her boyfriend, Perry Muth ’17, were driving on I-66 in northern Virginia. The couple, who met as juniors when they were neighbors at The Colony apartments, had passed the afternoon at Burke Lake. They enjoyed spending time together outdoors, and at TU they’d often hike at Oregon Ridge State Park or Loch Raven Reservoir, or even steal a quick getaway to the dog park at Lake Roland. They’d stayed together after graduation, and on what was a lovely sunny Saturday in October 2017, life couldn’t have been much sweeter.

As her Ford Escape emerged from a highway overpass—Harris behind the wheel, Muth in the passenger seat — tragedy fell on them from the seemingly clear blue sky, ending Harris’ life and changing numerous others forever.

A 12-year-old boy, police say, attempted suicide by jumping from that overpass—at

the exact moment Harris’ SUV came out from under it. He landed on the windshield of

the vehicle, which police estimate was traveling 55 miles per hour. She was killed,

while

miraculously, Muth was not hurt. The boy, probably the exact kind of kid Harris wanted

to dedicate her life to helping heal, survived as well.

“You’re angry that she’s gone, but we were never angry at him,” says Harris’ father,

Patrick. “Nothing’s going to bring her back. What we hope for is what I think Marisa

would want us to hope for. If this boy was or is still having issues, that someone

gets him

the help he needs.”

Photos of Marisa dot the Olney, Maryland, townhouse where she grew up and her parents, married for 28 years now, still live.

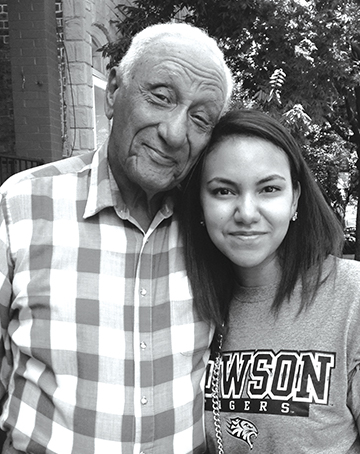

“That picture of Marisa and her grandfather—my father—Marisa loved that picture,” Patrick says. He’s sitting on the couch looking at a shelf next to the TV. Above the framed photo sits an urn that holds his daughter’s ashes. “That day made my dad so happy because Marisa was his pride and joy. I look at that and see two very happy people.”

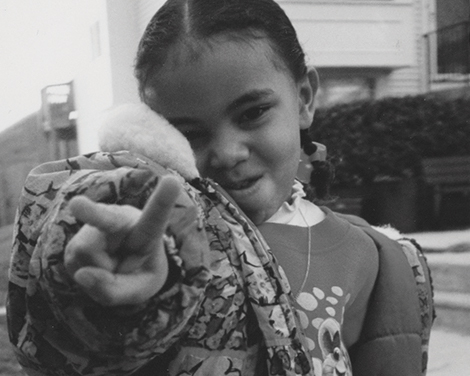

No matter what her age, Marisa’s magnetic smile usually shone through in photos. An only child, she was always up for playing with her younger cousins.

“I saw that in her early on,” says her aunt, Jane Wandless ’93. “She and my son are eight years apart, but just the way she would interact with him when he was 1 or 2 years old, even at that age I could see how special she was in the way she related to children.”

Harris played field hockey and flute while growing up, but she was a bit more academically inclined. A ravenous reader from elementary school on, she’d come home from book fairs with armfuls of paperbacks.

Her parents took her to visit several schools before she sided with her aunt’s alma mater over her parents’, the University of Delaware.

“We were very close, so I’d like to think that my influence was significant,” says Wandless, laughing. “I put Towson in the best light for her and just told her about my experience and how positive it was. I think it definitely had an impact, but in the end I think she made the decision that was best for her.”

By all accounts, Harris thrived at TU. She enjoyed its walkable campus and its proximity to Baltimore and Washington, where she traveled often to watch baseball games. Never a morning person, her grades soared after she was able to schedule mostly afternoon classes. She spent a semester abroad in Italy, studying in Florence and traveling to a dozen cities in that country as well as France.

Before her junior year, she was one of only a dozen students admitted to the Clinical Focus in psychology program. Its director, psychology professor Bethany Brand, taught her in three classes, including one in which students learn to lead a diagnostic psychological assessment of a prospective patient.

“She was an incredibly kind, compassionate person, and those are the sorts of traits that a really good therapist needs,” Brand says.

It was also during her junior year that she met Muth. Introduced by friends, they started dating in October 2015. The Charles Village Pub became their spot, but Harris seemed to have less time for bars and parties than he did.

“I actually had very bad grades before we started seeing each other,” says Muth, who now works for a military officers association in Alexandria, Virginia. “I didn’t want to go to CVP if she was just going to stay in all night, so I would end up staying in working on a paper that wasn’t due until the next week and end up getting a good grade on it.” (Crazy how that happens.)

Harris was comfortable in her own skin, which Muth found attractive. She could seamlessly

fit into a group, but also thrived by herself. She would talk to him about her desire

to become a child psychologist, and her kind, patient demeanor around kids was

evident to him. One day after taking in a baseball game in Washington, they strolled

to the National Mall, where Marisa promptly parked herself on a bench and struck up

a half-hour conversation with a 5-year-old. When it was over, Harris, the child and

the youngster’s parents all posed for a picture together.

Harris and her aunt grew even closer during this time. The two hung out at homecoming in 2016. They went to the football game, and Wandless took her niece to an alumni event at CVP.

“I just knew going forward we would be attending alumni events together,” she says. “It was unspoken between us, but I knew in my gut it would happen.”

Graduation day was another joyous milestone for the family. After watching the ceremony from the “nosebleeds,” they went to P.F. Chang’s, Marisa’s favorite restaurant. Two months later, Muth and Harris visited Wandless at her home in Chicago. They ate dinner at a Cuban restaurant, went on an architectural boat tour, and crossed watching a Cubs game at Wrigley Field off their bucket list.

“As an aunt the relationship changes over the years, from her being to a baby, to

a toddler, to a teen, to an adult,” Wandless says. “We had really gotten to that sweet

spot where we would go out and have a few drinks together and talk about hopes and

dreams and relationships. Unfortunately it just didn’t last long enough. Other than

it being heartbreaking and devastating that she’s not with us, I also mourn that fact.”

For Marisa’s parents, there are two distinct periods of life—before October 28, 2017, and after it. Patrick and Leigh hadn’t talked to their daughter that day, when in the late afternoon Muth’s mother called. There had been an accident.

As they raced toward Inova Fairfax Hospital, Patrick held out hope, while Leigh feared the worst. When they arrived, Marisa was already gone.

In the following days, as media coverage of the incident intensified, both the Virginia State Police and Fairfax County prosecutors concluded that the 12-year-old boy had purposefully jumped off the overpass. But the boy’s family didn’t allow him to be interviewed by law enforcement, and the police could not compel him to do so. In December 2018 The Washington Post reported that authorities at his school were advancing a theory that he accidentally fell over the overpass’ three-foot guardrail.

For Harris’ parents, this ripped open a still-raw wound. No charges were filed against the boy, and Patrick and Leigh didn’t advocate for any. Their concern now is simply that the boy—the jumper—receive the help that he needs.

It’s what Marisa would have wanted.

“I always think about the different scenarios that could have happened on that day,” Leigh says. “If she had survived and the boy didn’t I think she would have been devastated. If she had survived and the boy had survived, she would have made it a point to do whatever she could to help him. Maybe she would have tried to reach out to the family. But you can’t go down the what-if road.”

For Marisa’s father, details about the tragic incident are all background noise anyway. His daughter is gone, and nothing can bring her back.

“I always tell people that she did more in her 22 years than I did in my 54,” says Patrick, while petting the family’s energetic 8-year-old soft-coated Wheaten terrier Max, whom Marisa cherished. “She just grabbed on to life and rode it through whatever direction it was going to go. My regret is over the potential that’s lost.”

Life lurches forward. It’s different for Patrick and Leigh since October 28, 2017. Emptier. But they’re enduring. They started a fund in Marisa’s memory at the National Alliance on Mental Illness, where her application to work as a volunteer was submitted days before the incident. To date, it’s raised $9,660. Last summer they held a memorial service for Marisa, which they called a celebration of life, at a nature preserve in Delaware. Patrick made a slideshow for it that starts on the day of her birth, June 7, 1995, and progresses through her childhood into adulthood. In each successive photo, whether she’s posing with her boyfriend, a dog, a girlfriend, a relative or by herself, her smile radiates more than the last.

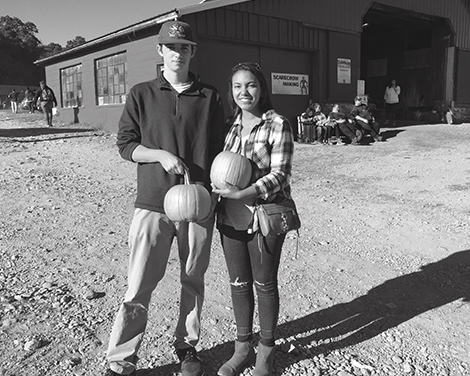

Playing in the sand at the beach as a toddler. Standing in front of the Washington

Monument as a teenager. Picking pumpkins with Muth, “pushing” the Leaning Tower of

Pisa as a beautiful young woman. These are the experiences that constitute a life

well

lived, even if it ended far too soon.