TU faculty focus on inclusion in mathematics

TU professor kickstarts national project born from student frustration

By Cody Boteler on June 28, 2020

When a visually impaired student told professor emerita Martha Siegel that the long wait time to get a mathematics textbook translated into Braille would lead to a delay in the student’s studies, Siegel decided to act.

“She had to delay not only that course but any course that depended on [Braille translation],” Siegel says. “She was very frustrated by that.”

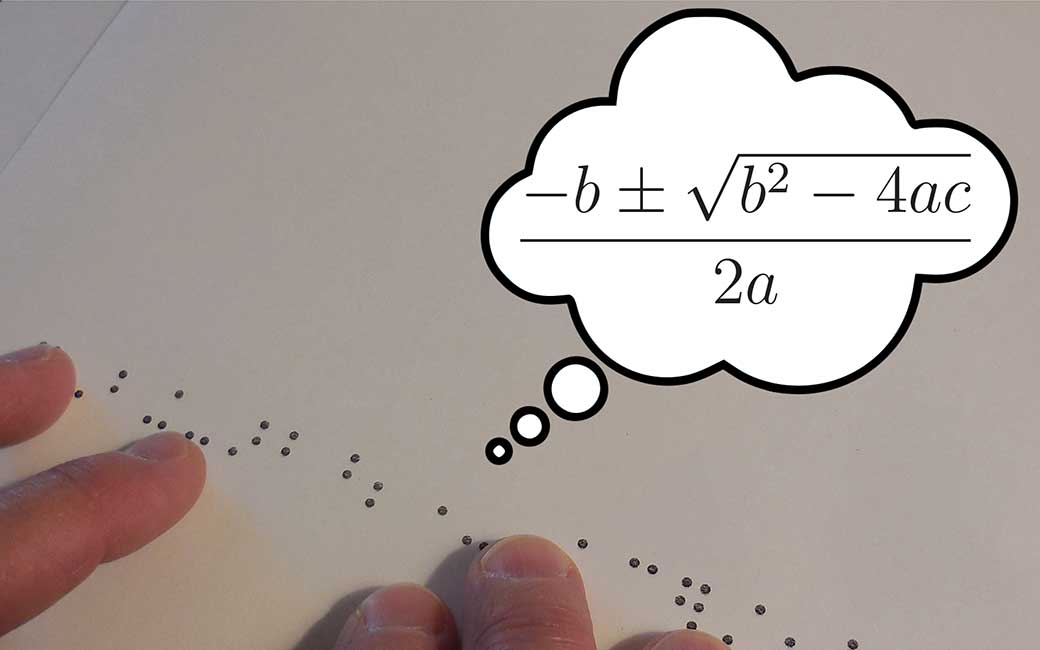

Braille is an alphabet that represents letters and symbols as raised bumps and is read by sense of touch.

While translating written words into Braille is straightforward, mathematical formulas, graphs and other figures are significantly more complicated to convert. Currently, textbooks are translated by hand by highly skilled translators—time consuming and costly work.

Knowing she did not have the technical skills necessary to develop translation software, Siegel asked around.

Alexei Kolesnikov, a professor in the Department of Mathematics, jumped in to help. For the last two years, he and Siegel have been part of a large, nationwide team working to automate translating mathematics textbooks into Braille.

Kolesnikov is the lead developer for the image processing in the project, which the American Institute of Mathematics (AIM) says is “the most difficult problem faced in producing Braille textbooks.”

“I was really appalled that in 2018, and now 2020, a freely available system to automatically translate mathematics text into Braille does not exist,” he says.

Mathematics can be difficult for people who are visually impaired to learn because of how formulas are presented. For a sighted person, comprehending a new formula can involve repeatedly staring at the formula to understand how the parts work together, he says.

For a person who is visually impaired, other methods of studying, like programs that read textbooks out loud, are unable to replicate the experience of intense visual study, Kolesnikov says.

Braille translations allow a person who is visually impaired to move their fingers back and forth across a formula to aid comprehension, Kolesnikov says, much like a sighted person would look at a formula.

Siegel says the translating work is extremely important because those who are visually impaired can feel shut out of mathematics or science fields because of the high barrier to entry when it comes to textbooks and course material.

“It’s true that it sounds much harder to do this kind of work if you’re blind. But to exclude an entire portion of population from a full field of careers is outrageous,” she says. “Translating evens out the playing field.”

Siegel, who retired in 2015, has already been recognized for her service to the field, including guiding national conversations about applied mathematics curricula. Kolesnikov, who now directs the applied mathematics lab Siegel founded, called her one of his role models.

“Both in terms of professional achievements and civic engagement on the part of mathematicians. I strongly identify with that,” he says.

This translation project is the latest example of a hallmark of the TU faculty: its willingness to above and beyond to connect their students to resources and experiences they need to succeed.

In late 2018, UTeach professor Gail Kaplan invited TU alumnus Danny Salemie to one of her classes. Salemie, who teaches at the Maryland School for the Blind, brought some of his students to show TU students how to teach mathematics to people who are visually impaired.

Students at Towson University also have access to a wide range of accessibility and disability services and accommodations, including note-taking assistance, interpreting services and alternate formats for printed materials.

More information about Towson University’s Accessibility & Disability Services can be found online.

Photo credit: American Institute of Mathematics

This story is one of several related to President Kim Schatzel’s priorities for Towson University: TU Matters to Maryland and Diverse and Inclusive Campus.