Feature

History in our own backyard

Professors Danny Mydlack and Kelly Gray took sabbaticals to learn more about local history and share it with the world.

From its founding as Maryland State Normal School in 1866, Towson University has been an anchor institution for Baltimore and the surrounding region. It was the first teacher training institution in Baltimore, created to meet the growing demand during the years immediately after the Civil War for formally trained, high-quality educators throughout the state.

It immediately opened a model school in Baltimore to provide low-cost education to students while training its student-teachers; four of the first seven principals became local supervisors or state superintendents of the Maryland school system. Physical education faculty member Donald “Doc” Minnegan developed curricula and best practices for state and regional K–12 fitness programs and school faculty and staff supported local efforts during both world wars, organizing first aid training, rolling bandages and collecting supplies for U.S. troops.

TU faculty members have a deep connection to their students, so it’s natural that what faculty discovers while on sabbatical will be transferred to their classrooms and benefit their students.

By 1960, when the university became a liberal arts institution, the school had graduated or certified nearly 9,600 teachers, many of whom stayed to educate tens of thousands of Maryland schoolchildren.

Which is why when electronic media and film professor Danny Mydlack and history professor Kelly Gray recently completed sabbaticals focused on Baltimore and state history, it was a full-circle moment.

The idea of faculty sabbaticals has been around since 1880 when it was instituted at Harvard University. Leaves of six months to a year give faculty members a chance to develop their research, devise new teaching methods or focus on creative growth. TU faculty members have a deep connection to their students, so it’s natural that what faculty discovers while on sabbatical will be transferred to their classrooms and benefit their students.

Danny Mydlack and 'Black Chesapeake'

Danny Mydlack didn’t yet know that his future would be in academia when, at about 10 years old, his elementary school was chosen as part of a pilot program for a new technology: the video camera.

“The camera was a square about the size of a large, four-slice toaster,” he says. “It was attached—by a hose cord about the thickness of a vacuum cleaner hose—to the recorder, which was around the size of a wheelie suitcase.”

Despite its bulk, this new technology caught on and changed not only filmmaking but also Mydlack’s life trajectory.

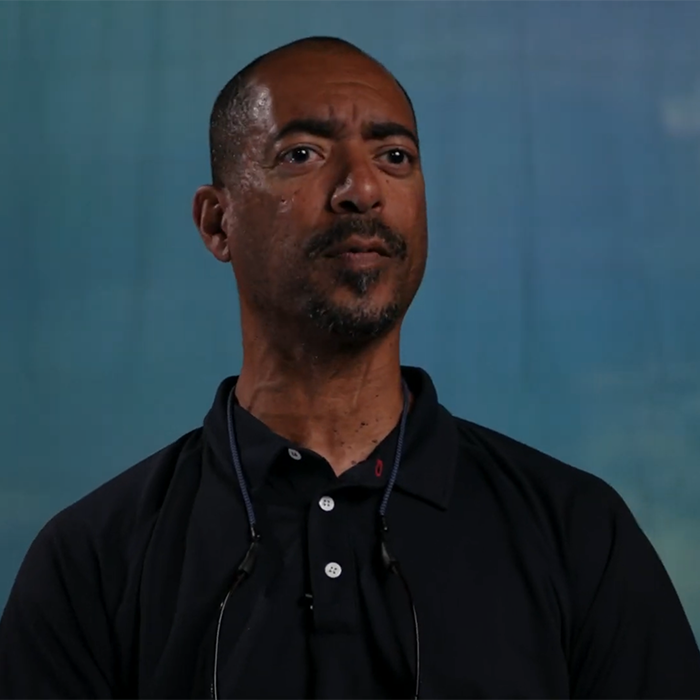

Danny Mydlack (left) met Marcus Asante (right) in a boat chandlery. Their conversation inspired Mydlack’s latest documentary, “Black Chesapeake.”

“I was already a painter and a drawer,” he says. “But the camera became like my backstage pass, so to speak, at the show of life, where you had an excuse to be hanging out on a sunny day on a street corner or poking your nose into an alleyway.”

During Mydlack’s prior sabbatical, he shot and edited “Outrigged,” an award-winning documentary about Jim Brown, one of the modern innovators of the multi-hulled boat—think catamarans, trimarans—that has a lineage going back thousands of years in the South Pacific. The nonagenarian has built a life sailing around the world and embracing the cultures he found. Brown has been legally blind his entire life.

Teaching what he learned to his students

In his classes, Mydlack has ample examples of his own work to demonstrate principles and techniques to his students.

“If you can use your own film, then you can say with complete authority, ‘Look at this shot. Let me tell you what you don't see,’" he says. “Or ‘Let me tell you how lucky I got here.’ Or ‘If you want to shoot like this, here’s the little trick I used.’”

Mydlack, who always works alone, now films with a 360-degree camera attached to a 12-foot pole that enables him to shoot the novel angles and different distances that are key elements in documentary filmmaking.

“The camera sees 360 degrees around in a sphere, and it records that, so you don't have to point the camera. Then you edit later,” Mydlack says. “We call it reframing. It allows a single person to get shots that you could never otherwise get—even with a big budget—economically and efficiently.”

If you can use your own film, then you can say with complete authority, ‘Look at this shot. Let me tell you what you don't see...’

Danny Mydlack

Mydlack was shopping for boat parts at a ship chandlery when the subject of his current sabbatical film walked up and said, "I have a story to tell, and I think you should tell it."

The man was Marcus Asante, and he wanted to share his experience as a Black sailor and how it fit into the larger tradition of Black people who are deeply tied to the Chesapeake Bay in a variety of ways.

Sailing the Black Chesapeake

Asante is the founder of Universal Sailing Club, which calls itself the only African American sailing club on the East Coast. He has a deep commitment to maritime education and decades of experience in boat maintenance, marine systems and boat sales. He has braided his abilities and passions into the Marine Arts Workshop, land- and sea-based programs he founded that provide life and trade skills to youth and young adults.

Each year in the fall the Seafarers’ Yacht Club, founded more than 50 years ago by working-class Black men, holds a two-day regatta for its members. Photos courtesy of Danny Mydlack.

“Over time, I realized how intelligent, resourceful and talented [Mydlack] is in filmmaking and in teaching,” Asante says. “The way he talked to me, I can almost see him in the classroom. I could see his deep love and care for the subject and for the outcome of the film.

I felt it was important to share the legacy of the boatman who knows the ancestors, who knows the shared history and the modern story.

Marcus Asante

“I felt it was important to share the legacy of the boatman who knows the ancestors,

who knows the shared history and the modern story. I had been in Baltimore for over

30 years, and I felt it was time for me to extend my own experiences to do that.”

Mydlack describes his film, “Black Chesapeake,” in part, as a portrait of Asante’s

mind.

“Marcus had this jumble of passions that he saw as all of one cloth,” Mydlack says. “Right from the get-go, I chose to see it as a fabulous collage that within would have a sense of meaning and honor.”

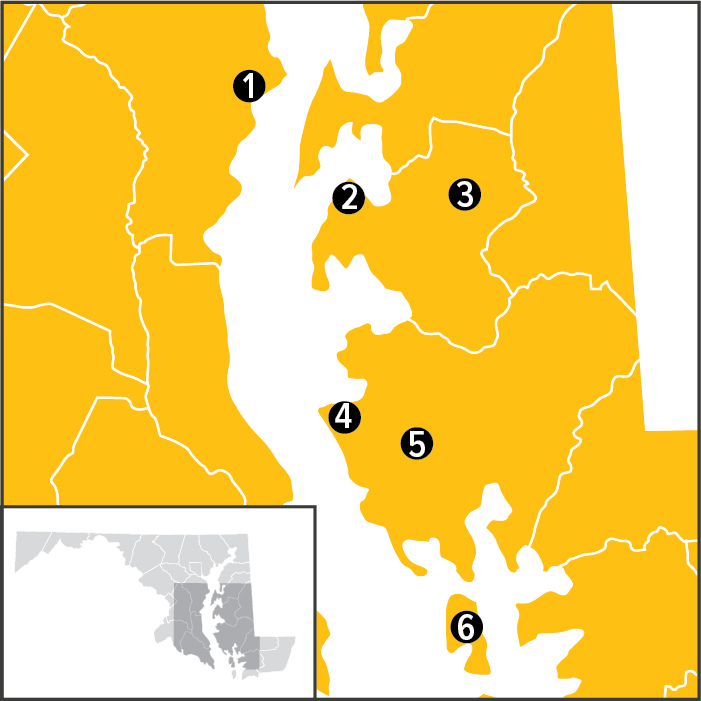

He and Asante filmed in six locations:

- the Seafarers’ Yacht Club’s annual regatta in Annapolis

- spots on the Choptank River on Maryland’s Eastern Shore used by Harriet Tubman as part of the Underground Railroad

- the headwaters of the bay near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- the Souls at Sea Celebration in St. Michael’s, Maryland

- the Dartmouth, Massachusetts, Historical Society, interviewing scholar and activist Lee Blake about prominent Underground Railroad conductor Nathan Johnson, who helped Frederick Douglass find freedom

- Cuttyhunk Island off the coast of Massachusetts, which was the home of Capt. Paul Cuffe, a Black American shipowner and an influential figure in the 19th-century movement to resettle free Black Americans in Africa

“Everything I shot turned out to be a revelation,” Mydlack says. “The Seafarers’ Yacht Club members dressing up in uniform and extravagant and disciplined boat parades just for themselves. The Souls at Sea ceremony overseen by an African holy man to appease and celebrate the living ghosts of the waters. Even Marcus’ story of kayaking in the Inner Harbor, between sugar freighters where he could easily have been run over or killed.”

But a constant throughout the film is Asante, a man Mydlack called his chaperone to the Black Chesapeake.

'Black Chesapeake' and the Underground Railroad

1

Annapolis Harbor - site of the Seafarer’s Yacht Club Annual Regatta

2

St. Michaels - location of the Souls at Sea Celebration (Fogg’s Landing)

3

Gilpin Point - one location on Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad water route; where enslaved Joseph Cornish escaped and started his journey to freedom

4

Taylors Island - where Harriet Tubman helped three of her brothers to freedom

5

Buttons Creek - site of Jane Kane’s escape to freedom, where she married Ben Tubman, Harriet’s brother

6

Hooper Island - the southern-most area of Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad water route

“Marcus embodies some of the core unresolvable class tensions of the city of Baltimore,” Mydlack says. “For the last 100 years on the Chesapeake, boating and yachting has been seen as a very exclusive, expensive insiders’ club that is traditionally white.

“People of color not only have worked the waters of the Chesapeake, but there are a lot of Black watermen and people that support Black water businesses,” he says.

“There are also and have been people of adventure, of achievement, of poetic grace. We just don't know about them. In some ways, theirs is a much more vibrant history because they've been doing it against all odds.”

Digging into Baltimore history

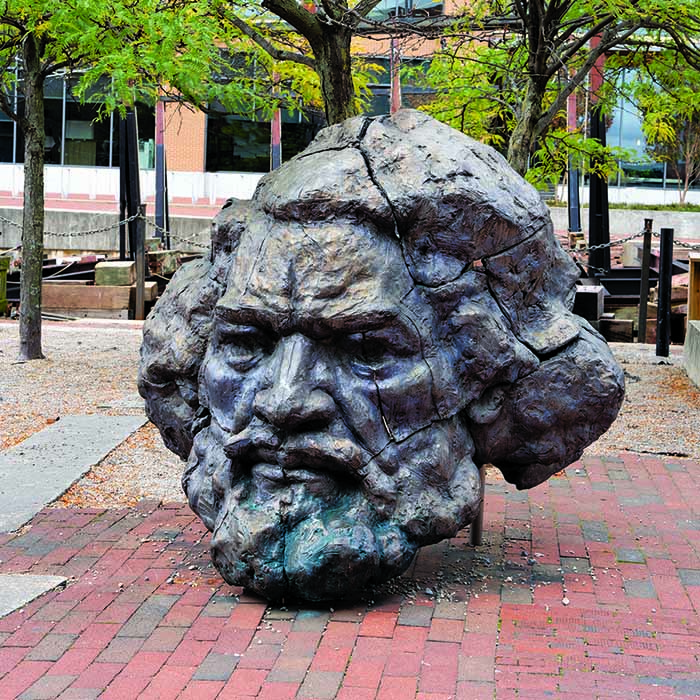

Frederick Douglass plays a role in Mydlack’s documentary footage and has a place in the manuscript evolving from Kelly Gray’s sabbatical work on Baltimore City in the 1820s–1840s.

“Frederick Douglass bought a book at a bookstore in Fells Point in his early teens,” Gray says. “And when he ran away, this is one of the few things he took with him. It helped him learn to read and contained arguments against slavery, so it almost certainly was important in helping him develop his ideas and speeches.”

(1) Professor Kelly Gray stands in front of the sallyport behind the Robert Long House, which is the oldest surviving residence in the original city limits. (2) The Thames Street Oyster House occupies the location of a bookshop where a young, enslaved Frederick Douglass bought a copy of “The Columbian Orator,” which taught him about freedom and resistance and gave him the rhetorical tools he needed later in life.

The bookstore’s address, No. 28 Thames Street, remains and is now home to the Thames Street Oyster House (renumbered 1728). Other buildings still standing sentinel that Gray has researched include the University of Maryland–Baltimore’s medical college building, now called Davidge Hall, and the Robert Long House, at 812 S. Ann St. Built in 1765, it is the oldest surviving residence in the original city limits.

She notes other places have disappeared entirely, like the Marquis de Lafayette’s tent site during the American Revolution, on top of which presently stands the Baltimore Basilica—whose primary construction phase ended in 1821.

Telling the city's whole history

A few years ago, she came across a liberal arts capstone course at TU on the topic “Edgar Allan Poe’s Baltimore” and was intrigued. Reviewing available literature, she noticed slices of Baltimore life being covered—like the beginning of Poe’s short story writing career in the early 1830s. But the native Baltimorean sensed a larger story.

“There was nothing that really looked at the whole city at that time,” Gray says. “I thought that would be an interesting story to tell; not just of what was going on but how different people related to each other, the city’s geography and, in antebellum Baltimore, we see the main themes for the whole country.”

Kelly Gray at the Robert Long House on Fells Point.

Gray cited concepts like the transportation revolution playing out in building the B&O Railroad to compete with the Erie Canal and slavery and abolition as seen through the conflict between Maryland being a slave state but having enough opposition to maintain a healthy abolitionist newspaper.

“I've always been deeply interested in writing, and history is what I do,” she says, “but I really like helping students develop the skills to do solid research and writing. That will help them at Towson and beyond. Also, it is important to me to emphasize that things are knowable and then teach how to know and communicate them.”

I thought that would be an interesting story to tell; not just of what was going on but how different people related to each other, the city’s geography and, in antebellum Baltimore, we see the main themes for the whole country.

Kelly Gray

In her research, Gray is often captivated by information that seems like something small, but when she pulls a thread, unravels into a much bigger (and occasionally gossipy) story.

“I found one item announcing that the son of the man who owned the nicest hotel in town had married the daughter of a local wealthy family,” Gray says. A wedding announcement may seem run of the mill, but then she “found that their subsequent divorce had been widely written about [then] because it was a significant case. Their reason for divorce didn't fall into the existing legal grounds. But one of her lawyers was Roger Taney, who later joined the Supreme Court. The divorce was granted.”

The deeper she digs into her research, the more she sees evidence that the Baltimore and Baltimoreans of today aren’t that different than those in the early 1800s.

“The neighborhoods we see today had started to form,” Gray says. “In fact, The Baltimore Sun was established in 1837 in Oldtown [today bordered by Orleans Street to the south and Eager Street to the north], and people were not buying the paper in Fells Point because they thought they would have to come all the way over to Oldtown. The paper had to run ads saying they’ll deliver.”

And while antebellum Baltimore doesn’t hold a candle to the quirky reputation the city has today, the seeds were being sown. Citizens enjoyed their horse racing, but they also enjoyed attending museums of oddities and seeing Apollo, the dog who could play dominoes. Gray is still in her research phase, but she does have a goal for what she wants readers to take away from her writing.

“In the era I'm studying, Baltimore was the third-largest city in the country,” she says. “Just prior to this period, on his presidential inaugural tour, George Washington had proclaimed Baltimore as the ‘risingest’ town in America. History doesn’t have to be about a war, a huge theme like the American West or a famous political leader to be a good read. Sometimes you can find a fascinating story in your own backyard.”

Baltimore Walking Tour

By Kelly Gray

So many buildings from Baltimore’s bygone eras are, of course, gone. But it’s remarkable how many structures from Baltimore’s antebellum era remain.

Here are some suggestions for places to visit.

The Ship Caulkers’ Houses

612–614 South Wolfe St.

- These wooden structures, built around 1797, were the homes of four free Black ship caulkers in the 1840s and 1850s. (Caulkers filled in gaps between the planks on ships, to ensure they were watertight.) A project is underway to restore these examples of antebellum working-class housing.

The Robert Long House

812 South Ann St.

- In the 1760s, Long, a young merchant, bought this land from Edward Fell, the neighborhood’s namesake. The house, completed in 1765, is the oldest extant residence in Baltimore.

The Thames Street Oyster House

1728 Thames St.

- In 1830, this was the site of Nathaniel Knight’s shop, where 12-year-old Frederick Douglass—then Frederick Bailey—bought a copy of “The Columbian Orator” for 50 cents. This volume, written by an antislavery Northerner, familiarized Bailey with debate regarding the abolition of slavery.

The Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park and Museum

1417 Thames Street

- The staff of this museum do a great job of conveying to visitors what Fells Point was like in the antebellum era—the workers, the buildings and the ships.

First Unitarian Church

12 West Franklin St.

- Many churches from the antebellum era endure, including this one designed by Maximilian Godefroy. Completed in 1817, it was the nation’s first Unitarian church.