Feature

Seeing the Good

At age 44, Henry Jackson was running one of the top money management firms in the state. Then he went blind.

Henry Jackson has the kind of quiet confidence that makes you stop and listen.

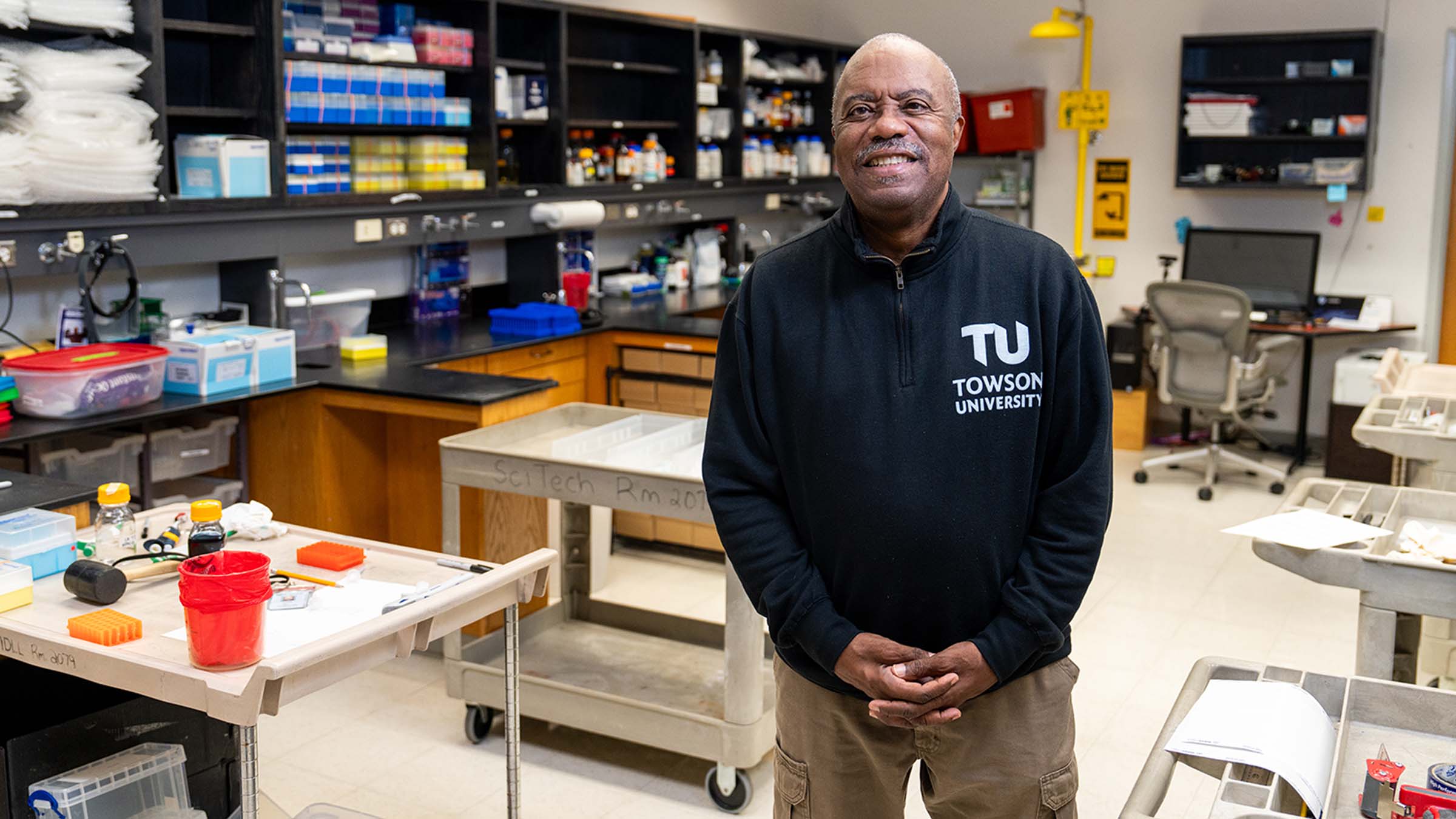

Today, sitting in a lab at TU’s Center for STEM Excellence, his kind eyes and calm voice hint at a familiarity with adversity and the wisdom it can bring.

Indeed, it was Jackson’s experience with success, illness, loss and reinvention that gave him the patience and perspective to become an outstanding and valued mentor at TU.

It didn’t come easy.

The child of an Army master sergeant and schoolteacher raised in the segregated South, Jackson learned about privilege and perspective from a young age. Growing up, he recalls visiting downtown Baltimore with his family and being allowed to enter stores but not make purchases.

Rather than dwell on the discrimination, his parents preached education and self-reliance as tools for combating it. To prove the point, they enrolled him in one of the nation’s leading military boarding academies.

Persistence pays off

When a 14-year-old Jackson arrived at Fork Union Military Academy in 1970, he was one of just a handful of Black students.

He made a name for himself, embracing the school’s high standards for discipline and discovering an interest in science. He graduated as a distinguished cadet and enrolled at Lincoln University as a pre-med major but by graduation had decided to pursue finance instead.

He found a job as a floor broker at a firm in Owings Mills and worked 80-hour weeks, studying the markets in the early mornings, working the floor when markets were open and cold-calling prospective clients in the evenings and weekends.

It was Jackson’s experience with success, illness, loss and reinvention that gave him the patience and perspective to become an outstanding mentor.

The military-school persistence paid off.

Jackson moved up the ranks, learning the ropes at a boutique firm in Towson before establishing his own company, Banneker Capital Management. Named after mathematician and author Benjamin Banneker, the firm managed investments for high-net-worth clients.

Jackson was the face of the firm, bringing in new business and identifying investment opportunities with the same intense focus that brought him success in previous roles. It enabled him to provide a comfortable life for his wife, Angela, and their two young children, Jared and Kayla. He was 44 years old, happy, in love and more successful than he'd ever dreamed.

Then his world went dark.

Navigating life without sight

It came like a freight train, steady and unyielding.

First, Jackson noticed he couldn’t see well while driving at night. Then his vision got progressively blurrier during the day. He’d visit the doctor for prescription glasses but his vision worsened again long before the next visit was due.

Eventually, he discovered the problem.

A progressive disorder called keratoconus was causing Jackson’s corneas to thin, reducing his eyesight until at one point he was seeing 20/400—double the threshold that’s considered legally blind.

I didn’t want to pout about it. I was just trying to figure out what I could do.

Henry Jackson

Doctors at multiple clinics said his best option was a full corneal transplant—an invasive procedure with a long recovery time and a 62% 10-year success rate. Struggling to manage his firm’s jampacked workload alongside his new disability and with little hope for a long-term resolution, Jackson released his clients and closed his firm.

It was a major life change.

His wife stepped up at work, taking on extra shifts as a flight attendant to provide for the family. Jackson stayed at home, trying to care for Jared and Kayla as he learned to navigate life without sight. He’d relished the role of doting father, but now it was the kids guiding him through chores and school drop-off. Once they were at school, the typically regimented businessman felt he could do little but sit and wait for their dismissal.

“Those were low moments,” Jackson says. “I didn’t want to pout about it. I was just trying to figure out what I could do.”

Jackson began to mentally map each room in his home so he could navigate it independently. He learned to carefully choose places for each of his belongings so he could locate them without assistance. He created workarounds for as many tasks as he could. Two years passed.

Maintaining his career at TU

Then one day Angela flipped through an in-flight magazine and came across a story on the Boston Foundation for Sight (BFS), a nonprofit research lab and clinic dedicated to treating diseases of the cornea. The clinic offered innovative treatment for Jackson’s condition, using custom prosthetic lenses to mimic a healthy cornea and improve vision. They booked an appointment.

Within days of getting treatment, Jackson began to see again.

“It was like someone turned the lights back on,” Jackson says. “I could see my wife. I could see everything. I thought, ‘I’m back.’”

With his vision restored, Jackson had a new lease on life—and he decided to use it to pursue his passion for science. He went back to school for lab certification and secured a job at the Towson University Center for STEM Excellence, a K–12 outreach program that prepares Maryland students for college and careers.

As a lab technician, he prepares experiment kits for distribution to schools, trains staff on lab techniques and takes extra care to help the center’s interns—many of whom come from underserved communities—see a future in STEM.

Working with Henry is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me ... through it all, he gave me compassionate and direct feedback that guided me toward success. It’s shaped my adulthood.

Chakya Browning, Jackson’s former intern

“He’s phenomenal at meeting our students and interns where they are and giving them the extra support they need to be successful,” says Mary Stapleton, director of the TU Center for STEM Excellence. “He’s faced so many challenges and he just will not allow himself or others to not overcome those challenges.”

Henry Jackson in the TU Center for STEM Excellence.

Leaving a Legacy

In his 17 years at the center, Jackson has mentored more than 50 students and interns. Many of them are enrolled in the same lab certification program where he embarked on his second career. Like him, most are new to STEM and eager to succeed in their chosen field.

Jackson has mentored more than 50 students, most of which are new to STEM.

Jackson takes time to demonstrate lab procedures, teach professional skills and demystify techniques. He combines his military-like focus with the compassion of someone who’s been in their shoes to teach the interns lab precision and professional determination, going above and beyond to put them on the path to success.

He combines his military-like focus with the compassion to teach lab precision and professional determination.

“Working with Henry is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me,” says Chakya Browning, a former intern of Jackson’s. “He showed me how to build good habits and how to conduct myself in a professional environment. He even used his day off to take me to the BioTechnical Institute of Maryland so I could learn more about their training programs. And through it all, he gave me compassionate and direct feedback that guided me toward success. It’s shaped my adulthood.”

Last summer, Jackson’s legacy of mentorship earned him the University System of Maryland (USM) Board of Regents Staff Award for extraordinary public service to the university or greater community. The award is given annually to just one of the more than 40,000 system employees. It is the highest honor bestowed on staff members by the USM.

It’s a special thing to watch young people build their confidence and realize they can achieve their dreams

Henry Jackson

Jackson says he was stunned and humbled by the honor. To him, mentoring is simply a way of affording others the same second chance that he got.

“It’s a special thing to watch young people build their confidence and realize they can achieve their dreams,” Jackson says. “I’m honored to help them get to that next level so they can find success.”

Every two years, Jackson travels to BFS for a five-day treatment. While the science keeps advancing, it hasn’t outpaced his keratoconus. These days his corneas are so thin that even with the prosthetic lenses, he no longer sees well enough to drive. Yet his future is crystal clear. Day after day—even if he retires—Jackson says he’ll keep coming back to the center in some capacity to share his quiet wisdom with those in need.

Old habits die hard.