As a child, he developed a passion for collecting and caring for reptiles.

Feature

Cover’s Story

Few people have been more integral to the National Aquarium’s success than its recently retired general curator.

Jack Cover ’79 died on Wed., Jan. 7, 2026, after a brief illness. He had been retired for just over a year, after 37 years at the National Aquarium. Aquarium staff members have created a retrospective to celebrate Cover’s life and career. The TU community offers its deepest condolences to the Cover family.

Jack Cover is walking through the maze of exhibits at the National Aquarium in Baltimore with the air of a proud papa. But none of the countless kids who are zigzagging their way around, marveling at the fish tanks and reptile enclosures are his children. It’s the exhibits themselves that he helped father.

In January, after 37 years at the aquarium, Cover ’79 retired. Well, kind of.

A few days after officially leaving his position as general curator, in which he led the creation of some of the aquarium’s most iconic installations—Amazon River Forest, Australia: Wild Extremes, Blacktip Reef, and the newest, Harbor Wetland—he’s back. In addition to volunteering with Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources, he plans to lend a helping hand around the aquarium every now and then. The place is a part of his very fabric.

As he points out black drum fish, which, he says gleefully, have bite-crushing power greater than crocodiles, he bends down to pick a piece of trash off the ground.

Caring about all aspects of the aquarium is second nature to him. Cover, 68, meets staff members and visitors alike with a warm smile or a nod, but his widest grins are reserved for when he talks about the aptly named pig-nosed turtle, air-breathing lungfish and alien-like wobbegong shark that surround him.

Left: Cover teaching a possible future herpetologist (Photo: Philip Smith/National Aquarium). Right: Working on Harbor Wetland (Photo: Lauren Castellana).

That’s been Cover’s primary goal since he joined the aquarium as a herpetologist in 1987.

He took over as general curator in 2004 and has spent the last two decades ensuring that it remains Maryland’s most popular paid tourist attraction, with more than 1 million visitors annually.

Not everybody even gets to go on a field trip to the Chesapeake Bay. So let’s bring these habitats to the people.

Jack Cover

His final project might just be his crowning achievement: Harbor Wetland, a 10,000-square-foot outdoor exhibit between piers 3 and 4 in the Inner Harbor that opened last year. With 39,000 grasses and shrubs, it’s a floating habitat for fish, crabs, turtles, birds and myriad other species.

Even river otters have been spotted frolicking in its marsh.

“Quite frankly, I don’t think the project would have come to fruition without Jack,” says Jennifer Driban ’07, ’11, the aquarium’s senior vice president and chief mission officer. “Jack was involved from start to finish through every element of that project for almost 14 years.

He has such an array of knowledge of not only the animals that are in the aquarium but also the native species that call Maryland home. It’s a wonderful example of his lasting impact on the aquarium.”

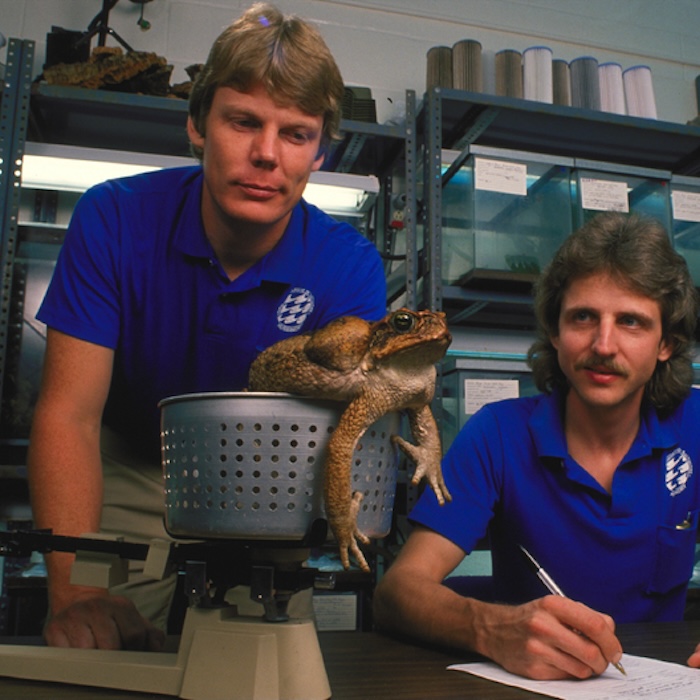

(Photos: Philip Smith/National Aquarium)

A lifelong passion for reptiles

Not too many kids who grow up in Baltimore—or any other place, for that matter—have a pet caiman. But a young Cover once bought one at a department store (that sort of thing being completely normal in the ’60s).

When it eventually grew from six inches to five feet long—a bit too big for the Hampden rowhouse where he lived with his parents and three siblings—he had to donate it to a reptile exhibit in Florida. The alligator-like creature was the latest in a line of out-of-the-ordinary pets that started with an innocent knock on his family’s front door.

“I was 6 or 7, and the school bus driver brought this ring-necked snake by,” he recalls. “A boy had brought it on the bus and was terrorizing the girls with it. He thought my brother and I should have it. For some reason, my mother agreed to it.”

The snake was placed in a wide-mouthed gallon jar on the kitchen table, where Cover sat, transfixed.

“The colors of it and the black and red tongue going in and out; I must have spent an hour just staring at him,” he says.

It was love at first sight.

Cover quickly became obsessed with all kinds of scaly and slimy animals, riding his bike to the library to check out books on reptiles and making frequent trips to the Reptile House at the nearby Maryland Zoo to gaze at them.

He also was a collector, capturing snakes, frogs and turtles from undeveloped parts of the city like the Jones Falls, Wyman Park and Stony Run. He’d keep them in his house, and even though his parents didn’t necessarily understand their son’s passion, they encouraged him to pursue it.

His college years at TU, he says, were life changing.

“For me it was a dream,” he says of his herpetology class, trips to collect specimens in the wild and introduction to other likeminded students. “I became part of a rich community of biologists and got to explore the academic side of learning about these animals.”

As a child, Cover captured snakes, frogs and turtles from undeveloped parts of the city.

Don Forester, a biology professor at TU from 1974 to 2005, was a teacher and mentor to Cover. The two remain friends today.

“Jack was like a savant,” Forester says. “He was so into herpetology—all he lacked was a formal education. He was constantly out in the field collecting things.”

Years later, the two lived a few blocks from one another in Harford County.

“I went over to his house and his son, Zak, was there,” Forester says. “He says, ‘Where do you keep your snake room?’ I said, ‘My what?’ Jack had converted one of his bedrooms into his snake room. He was studying patterns in eyelash vipers. He had 30 or 40 little aquaria in there each with a viper. He was breeding them and looking at the transmission of color patterns. I suspect his neighbors had no idea.”

In his mid-20s, Cover was injured on the job. The job being extracting venom from king cobras, scorpions, tarantulas and other venomous animals to be used for research and making antivenoms. Seems a Mexican beaded lizard had leapt past a dead mouse that was being fed to him and latched on to Cover’s hand.

Getting the lizard to let go was difficult; while it was attached, it was pumping venom into his body. By the time Cover made it to the hospital, he was having an out-of-body experience. He was throwing up bile from his gall bladder, and his life was in serious jeopardy.

“They gave me epinephrine to counteract the components in the lizard’s venom, and I went from feeling like, ‘You dummy, you died at a young age,’ to euphoric. I was ready to eat a hamburger. It was very strange, but an amazing firsthand lesson in biochemistry.”

The incident convinced him that a career change was in order, so he took a position as a reptile keeper in the Herpetarium at the Fort Worth Zoo. By this time, he was married to his wife of now 42 years, Carole, who’s a very understanding woman. They shared their Texas house with some of Cover’s critters.

“I had all these different snakes that I was breeding and learning about,” he says. “It was a little bit too hot for even the tropical snakes in Texas. This house didn’t have air conditioning, so I went out and bought a window unit, and it went into the snake room.”

Cover had always dreamed of working at the National Aquarium in his hometown, so when a position opened in 1987, he leapt at it. He was hired and began working on Hidden Life, part of the Upland Tropical Rain Forest exhibit. He traveled to Suriname—one of many trips all over the world—to evaluate the status of the wild population of poisonous blue dart frogs, which still are bred and displayed at the aquarium today.

“The blue dart frog is found in a few locations on the Suriname–Brazilian border. There are no roads, just Indigenous people there. First, we had to go to Paramaribo, the capital, and from there we had to take a bush plane about two and half hours over unbroken rainforest,” he says, describing an Indiana Jones-like expedition. “We landed downhill on a muddy field then got in a boat for several days as far as they could go—it was the dry season.

Then we started walking across the Sipaliwini Savanna, to where this frog lives. We walked for another day, getting eaten by tiny insects called no-see-ums. Finally, you come to this place where there are no people but there are these bright blue frogs.”

The arduous journey was worth it. Over the years he lent some strawberry poison dart frogs to Forester, who used them in behavioral studies at TU that resulted in multiple published papers. After becoming general curator, Cover’s first major exhibit project was Australia: Wild Extremes, an idea he pitched.

Jack is the rare curator who appreciates all the complexities of what makes a truly compelling living exhibit ... He understands everything from species selection to habitat fabrication to the visitor experience

Robin Faitoute, former manager of exhibit development

He and his team started by traveling down under and taking countless photographs of the animals and the environments in which they live. He acquired animals through a variety of means (some from zoos and aquariums, some from private citizens) and worked with crews to ensure that the exhibit was practical for the animals and educational and entertaining for the public.

No detail was overlooked.

Doors were hidden by fabricated rock habitat and flora. Support beams were covered and finished by artisans to look like Australian sandstone. Hidden pumps created natural-looking waterflow.

“From an exhibit developer’s perspective, Jack is the rare curator who appreciates all the complexities of what makes a truly compelling living exhibit,” Robin Faitoute, former manager of exhibit development, told the aquarium’s publication Watermarks. “He understands everything from species selection to habitat fabrication to the visitor experience. Creating an impactful exhibit experience is complicated and takes time. He is committed to the process and to ensuring authenticity and accuracy.”

Jack Cover feeding breakfast to a yellow-footed tortoise. (Photos: Lauren Castellana ’13, ’23)

Advocating for Maryland’s turtles

Looking back on his career, Cover’s proudest accomplishment was working to pass legislation to protect Maryland’s state reptile, the diamondback terrapin.

In the early 2000s he learned that they were still being harvested and exported in large numbers to Asia. Cover and other aquarium staffers joined in an effort that ultimately resulted in Maryland ending its long history of commercial harvesting of terrapins.

It’s succeeded. Cover’s seen it with his own eyes. While working on Harbor Wetland, he’s witnessed diamondbacks swim into the habitat that he played a pivotal role in creating.

“There’s a misconception that the Inner Harbor is too polluted to support aquatic life. That’s really not the case at all,” he says. “If you’re a hatchling turtle, you’re sort of the chicken nugget of the animal world. Everybody wants to eat you. You’re soft and probably tasty. You want to go into the marsh grass and remain hidden until your shell’s big enough to eliminate some of those predators. That’s why we built these constructed habitats and floating wetlands. And then you start seeing crabs. You see northern water snakes. We are recreating habitats that existed here long before the city was built. We're in downtown Baltimore, but it's kind of like, if you build it, they will come."

My Next Guest … Really Loves Snakes

At first glance, Jack Cover ’79 seems an unlikely guest for a late-night talk show. Unassuming and academic by nature, Cover can appear to those who don’t know him to be more comfortable among his beloved snakes, lizards and frogs than people. But watch him interact with visitors at the National Aquarium, where he worked for 37 years, and you’ll see he has a natural way with two-legged animals as well.

David Letterman discovered this when Cover appeared on his “Late Night” show five times in the 1980s. Cover’s dry humor—combined with Letterman’s quick wit—led to many laugh-out-loud moments when Cover brought animals from the aquarium to Letterman’s studio in New York.

It all started when a PR person from the aquarium suggested to Cover that he send a demo tape to Letterman, who famously loved having animals—and their handlers—on the show. Although Cover was skeptical, he recorded it and much to his shock, was booked on the show.

“It’s funny because he was not a big fan of snakes, yet the producer said, ‘Go out there with a snake,’” Cover says of one of his appearances. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, there’s lots of ways you could become famous. You gave David Letterman a heart attack.’”

Letterman survived, and Cover returned as a guest several times. (Once, musical director Paul Shaffer led the band in a rendition of The Who’s “Happy Jack” when he walked on stage.) Everyone, it seems, got a kick out of his appearances.

"The biology department at Towson, they would all watch it,” he says. “I’d hear back from them that they loved it. My parents, through my whole life, it’s like, ‘It’s about time you got like a real job.’ But when you go on Letterman, they’re like, ‘We've been behind you your whole life.’”

Cover's appearance is approximately 17 minutes into the video above.

Behind the Scenes

We’ve never had a more aptly named cover subject than Jack Cover ’79 (though it’s pronounced cove-er).

Director of Photographic Services Lauren Castellana ’13, ’23, lead the photoshoot on the cover of the print issue.

“From the moment I was informed that our photoshoot would take place at the aquarium, I knew I wanted to capture a shot from the bridge overlooking Jack in the wetlands exhibit. This exhibit is remarkable, playing a vital role in supporting the harbor and local wildlife,” she says. “We were fortunate to have a sunny day, perfect for the cover shot.”

Career Highlights

1960s

1979

After sustaining a near-fatal bite from a Mexican bearded lizard, he was inspired to become a reptile keeper.

1987

Joined the National Aquarium as an herpetologist

1989

Featured on the Late Night Show with David Letterman

2004

Started his position as the aquarium's general curator

2007

Worked to pass legislation to protect the diamondback terrapin