Nazi book burning and confiscation campaign begins.

Web Exclusive

Saving the lost books of the Holocaust

TU librarians are leading a nationwide effort to identify, preserve and share thousands of Nazi-plundered texts before they’re lost to history.

As World War II came to a close, Allied forces discovered vast storehouses of art, books and cultural artifacts looted by Nazi soldiers. Among them were more than three million books and manuscripts; several thousand of which ended up at Towson University. Now TU librarians are leading a nationwide effort to identify, catalog and share them before they’re lost to history.

Identifying lost texts

In the late 1940s, the boxes arrived by the dozens at libraries and institutions big and small. They came without packing lists—just orderly packed books alongside a stack of nameplates recipient institutions were meant to affix inside. But many lacked the manpower to do so, much less tackle the tracking and translating necessary to properly identify and catalog them.

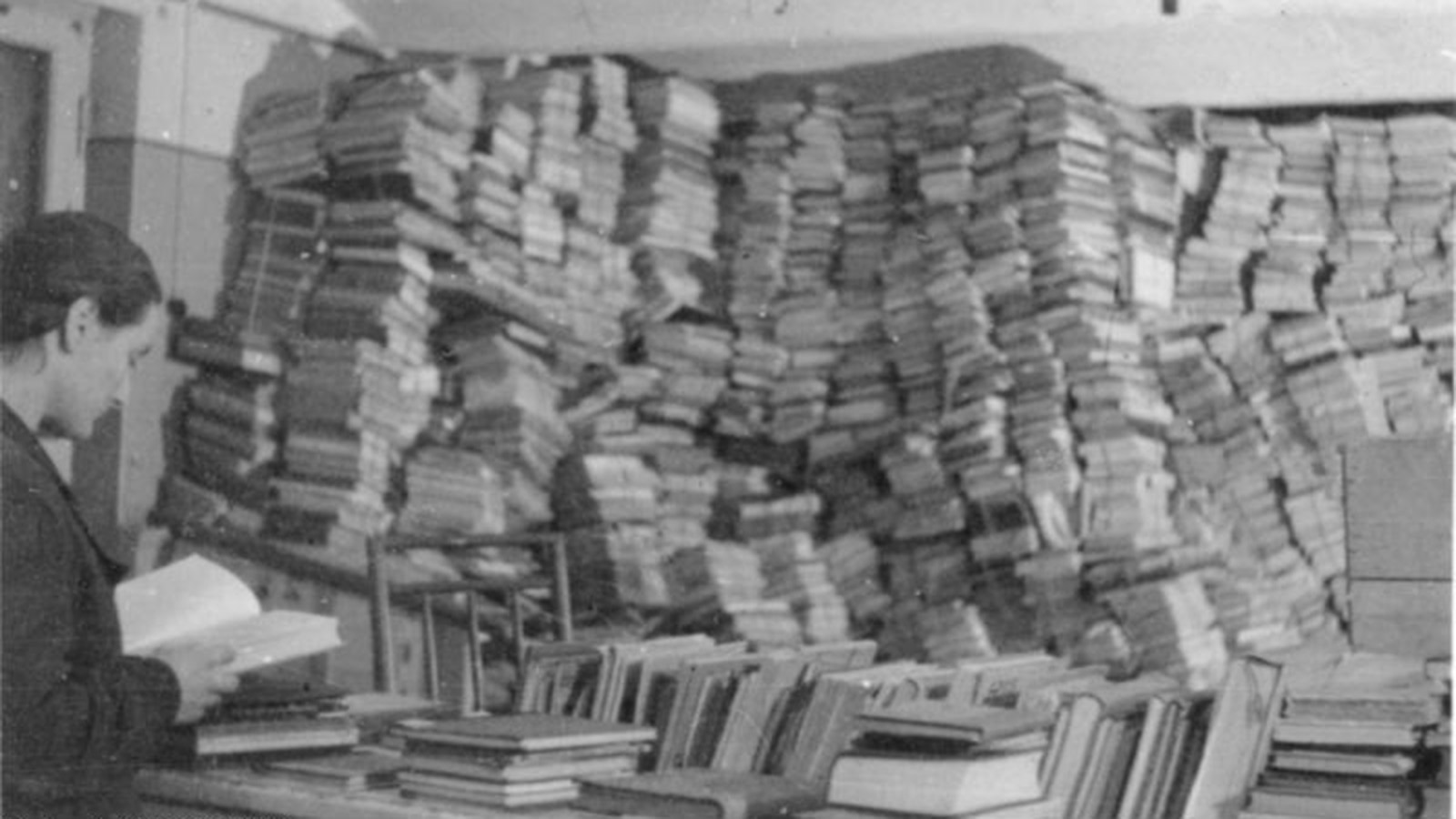

A warehouse of Nazi-looted books in Riga, Germany, November 1943. (Photo: Creative Commons)

Over the years, those texts trickled into their libraries’ general stacks without markings to indicate their historical significance. As time goes on, these unidentified books are at increasing risk of being withdrawn from collections and erased from history forever.

We must try to understand that history so we can better understand our present and our future.

Elaine Mael, Cook Library cataloguing librarian

TU’s role in preserving this piece of Jewish cultural history came about through its partnership—and later merger—with the Baltimore Hebrew Institute (BHI).

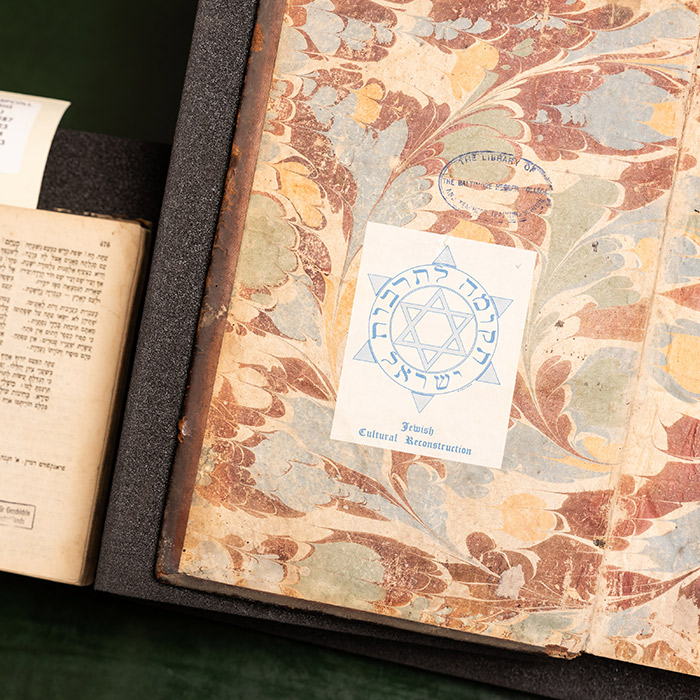

In the late 1940s, BHI—then called Baltimore Hebrew College—was one of 50 U.S. institutions selected by the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction organization (JCR) to receive a portion of the 500,000 books the committee could not identify or return to a living heir.

BHI received approximately 4,500 books ranging from historical texts in Hebrew to children’s books in Polish. Thanks to careful management, most of BHI’s books are catalogued and housed in TU’s Special Collections. Others weren’t so lucky.

Suzanna Yaukey, Joyce Garczynski, project coordinator Samuel Seliger, Elaine Mael and Ashley Todd-Diaz alongside books recovered from the Holocaust. (Photo: Lauren Castellana)

But many are still able to be saved. Dean of Libraries Suzanna Yaukey and librarians Elaine Mael, Ashley Todd-Diaz and Joyce Garczynski are working to create and disseminate best practices for cataloguing the books, establish a shared catalog for them and develop programming to share these culturally relevant artifacts with communities across the nation.

Nazi book theft and destruction

1933

1939

World War II begins.

1940

The Nazi organization forms the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce to seize cultural property, with an initial focus on books and documents.

1941

Nazi looting expands to include art and other objects.

1942

Looting becomes more widespread, with books stolen from families and community organizations.

1945

World War II officially ends.

1947

Jewish Cultural Reconstruction organization formed to return millions of stolen items to their rightful owners.

The best practices will include a stamp glossary and other shared resources to empower recipient institutions to identify and preserve the books. Once identified, information on the books will be combined into a national Holocaust book catalog to make them more accessible for historians, educators, students and citizens.

Thanks to a $250,000 Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant and partnerships with Brandeis University, the University of Denver, Yeshiva University and the Jewish Theological Seminary and support from TU’s Sandra R. Berman Center for Humanity, Tolerance and Holocaust Education, TU’s librarians are making inroads in preserving these texts.

“By increasing awareness about what books exist and what institutions have them, we make it easier for researchers and educators to find them and use them in their work,” says Todd-Diaz.

Keeping history alive

Identifying and cataloguing the lost Holocaust books creates opportunities to share them with local students and communities, where they serve as a starting point for dialogue and education.

TU students, faculty and staff can see the texts in the Cook Library Special Collections or at programs held in collaboration with the Berman Center, and Mael and Todd-Diaz regularly host white glove sessions with TU classes and local high schools to explore the books’ history.

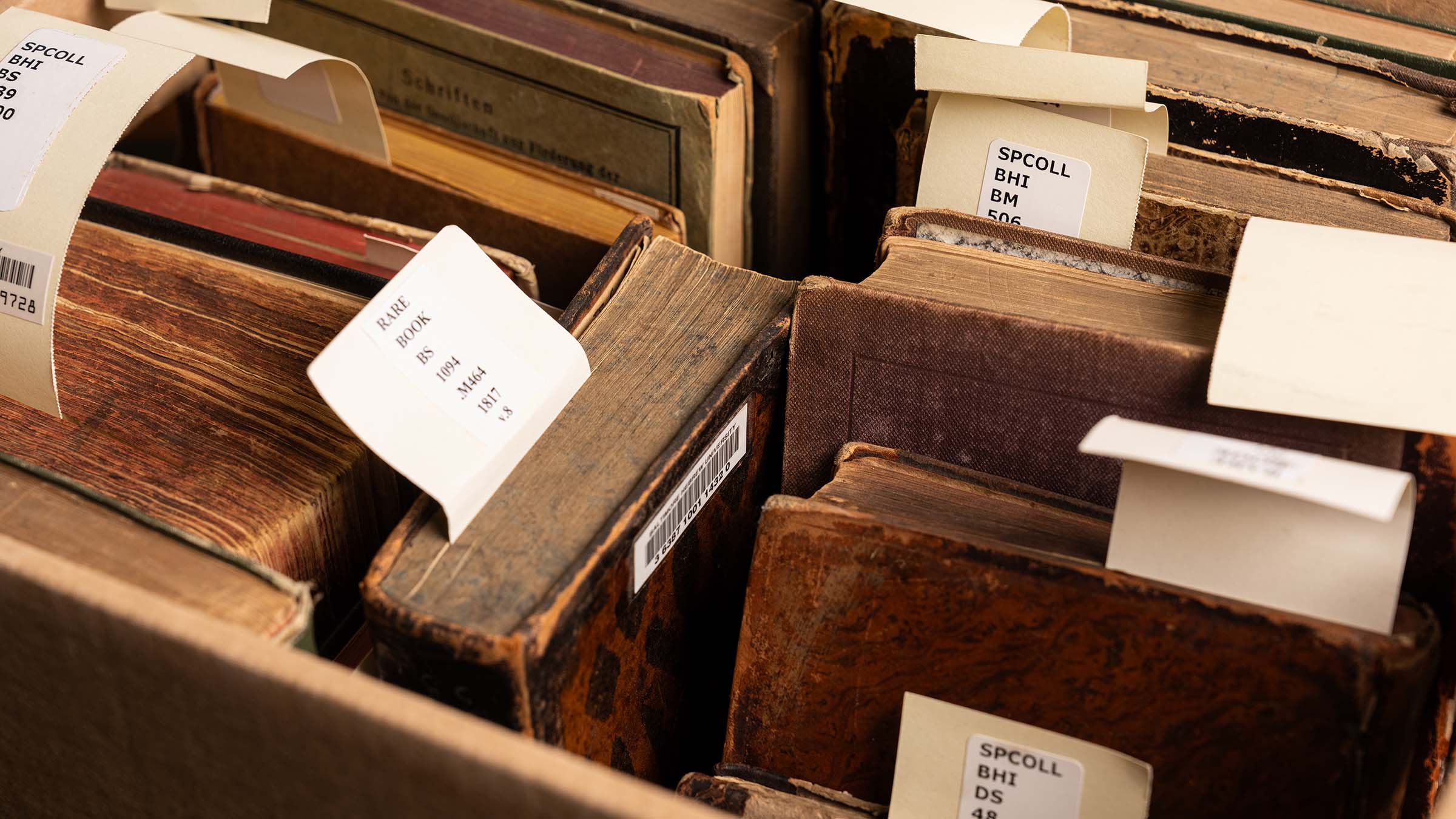

Books recovered from the Holocaust residing in TU's Special Collections. (Photo: Lauren Castellana '13, '23)

The grant is enabling them to build out this programming and add marketing tools to create a complete playbook from which recipient institutions nationwide can share the texts with their local communities.

The people who once owned these books may have been wiped away, but their artifacts are still here, and they bring us closer to understanding the history of what they endured,

Elaine Mael, Cook Library cataloguing librarian

Experience has shown the artifacts help their audiences personalize a historical event that continues to impact our world today.

“The people who once owned these books may have been wiped away, but their artifacts are still here, and they bring us closer to understanding the history of what they endured,” Mael says. “We must try to understand that history so we can better understand our present and our future.”

Introductory photo for this story: copyright Creative Commons.