A Catalyst for Change

When Catalina Rodriguez Lima ’06 saw the need for an office of immigrant affairs in Baltimore, she did what she’s done her whole life: She acted.

By Mike Unger

Catalina Rodriguez Lima is sitting in Teavolve in Fells Point, sipping a warm mocha latte on a chilly January afternoon. The cafe is about a mile east of Baltimore’s City Hall, where her professional career has been shaped; about a mile west of her house near Patterson Park, the beloved neighborhood she and her husband call home; and more than 2,900 miles from Cuenca, the Ecuadorian city where her unlikely journey began.

“Immigrants are here to have a better life,” she says. “That’s part of the reason why they’ve left their countries of origin. They’re extremely resilient, but they have barriers, and those barriers are challenging to address.”

She’s not talking about herself, but she very well could be. Rodriguez Lima’s story is similar in many ways to the millions of immigrants who come to this country every year. At 18, she left the only home she’d known in search of opportunity. But her remarkable accomplishments, achieved in such short order, differentiate her from the people she’s dedicated her life to serving. In 2014—at just 33 years old—she led the successful effort to establish the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MIMA). She’s the only director it’s ever had.

In 2013, she was named one of 50 women to watch by The Baltimore Sun, and, a year later, she was on the Baltimore Business Journal’s 40 Under 40 list. Rodriguez Lima, 41, appreciates the recognition but doesn’t let it distract from her singular focus: improving the quality of life for Baltimore’s immigrant population.

“What I am trying to do is carve out a space at a local level where we can think about the realities of these people that are trying to build a life like you and I.”

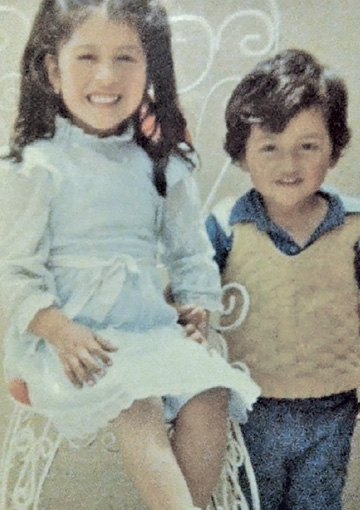

Cuenca is a city of about 660,000, perched more than 8,000 feet above sea level in the Andes Mountains. Rodriguez Lima was born and raised there and has fond memories of it (especially its mild climate). Her parents and younger brother still live there.

But during her teenage years, Ecuador was experiencing a bank crisis and inflation, making young people like Rodriguez Lima nervous about their futures.

“It was grim,” she says, “especially for someone who had just finished high school and was thinking about their next move.”

Rodriguez Lima had an aunt and uncle who lived in Baltimore County, so at the age of 18, she went to visit them for a summer. Her plan was to improve her English, so when she returned to Ecuador, she could find a job in the tourism and hospitality sector.

Although her language skills turned out to be not quite as proficient as she would have hoped, she became enamored with the United States and decided to move here at age 20. She lived with her family, attended Essex Community College and worked as a waitress. That experience changed her mind about the service industry, and she decided to get a student visa and transfer to TU.

TU, Rodriguez Lima says, was transformational for her. She majored in international studies, minored in Spanish literature and volunteered for several nonprofits, including Education Based Latino Outreach in Baltimore.

“That was a very important moment in my life because I realized how much need existed in the city and how communities were really struggling,” she says. “That was the first peek where I thought, ‘My career needs to be public service or nonprofit or community driven.’ It felt right.”

But for an immigrant without citizenship or permanent legal status, long-term planning is an unafforded luxury.

“There’s always a constant reminder that you have until X-date until your visa expires,” she says. “I remember coming back to Ecuador to renew my student visa. I had a car, I had an apartment, I had school, and I remember going to the U.S. embassy and thinking, ‘Oh my god, what if I don’t get a renewal? What am I going to do with all my stuff?’ But you’re young, and you take risks.”

That one paid off. Her student visa was renewed, and when she returned to Baltimore, she landed an internship in the office of then-Mayor Martin O’Malley. Eventually, her stellar work caught the eye of Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, then president of the city council, who hired her as a Latino liaison on her staff.

When Rawlings-Blake became mayor in 2010, Rodriguez Lima accompanied her to her new office in City Hall.

“When I met Catalina, I knew she had the spirit of a servant—she wanted to help people. I could tell that immediately,” Rawlings-Blake says. “I was raised to value public service…and I could tell that in this way Catalina and I were the same.”

Rodriguez Lima says she quickly realized that the issues Latino immigrants were facing were being faced by other immigrants as well. So in 2011, she pitched the idea of creating an office of immigrant affairs to her boss. Much to her surprise, the mayor said yes.

But that was just the beginning. Rodriguez Lima developed a task force that was charged with recommending to the mayor ways to make Baltimore a more inclusive, equitable and welcoming city for immigrants. The group, comprised of people from government, nonprofits, philanthropy and immigrant communities, examined the systematic issues government had in dealing with immigrants and tried to come up with solutions that made government more accessible.

“Language barriers impact every single system that you can think of in the city, especially for public-facing services,” she says. “Your water, your police, your permits, your parking tickets. Think about all the systems that are public facing that are not necessarily accessible to people because they don’t speak the language.

“A lot of programs are not designed for immigrants who are perhaps in mixed-status households, meaning they have a U.S. citizen child and parents who are undocumented. Because of that, agencies may not necessarily know whether the family qualifies. They may not know the types of alternative documents that immigrants, who perhaps don’t have a birth certificate or a passport, may have.”

MIMA was created to help solve some of those problems. The office does not deliver direct services to citizens; its focus is on overseeing the city’s compliance with federal regulations related to serving the immigrant population and improving the way city agencies work with immigrants.

“Catalina has a strong moral compass and is incredibly passionate about her role as a public servant and director of MIMA,” Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott says through a spokesman. “She takes pride in what she does and uses it as a platform to bring people together to do greater things. Her sense of humility and resiliency inspire others to focus on goals beyond their own self-interest. Most importantly, she loves our city and cares deeply about the people who live here.”

Along with leading an office that’s grown from two to six staff, Rodriguez Lima facilitates

relationships between the city and nonprofits. In 2015, she helped convince the Washington-based

Latino Economic Development Center to come to Baltimore. Since opening an office in

Highlandtown, the organization has offered almost $2 million in loans to small businesses

and for home ownership to more than 600 (primarily Latino) residents.

“Because of the need, at some point we would have figured it out, but Catalina was

very instrumental in connecting us to the right organizations in Baltimore,” says

Omar Velasco, chief of small business services and lending for the group. “She is

able to engage all the stakeholders and be a mediator so each party can talk to each

other and collaborate and get

the resources they need.”

Perhaps one reason Rodriguez Lima is such an effective leader in the immigrant community is because she has never forgotten that she is one herself. While she became an American citizen in 2019, she says will always consider herself Ecuadorian—and an immigrant—as well.

But these days, Baltimore is home.

“I love this city,” she says. “This city welcomed me. I love how quirky it is. I love its sense of community. I love how progressive it is. I love its people. I love how it is rough around the edges, and it’s not perfect. Because life is not perfect.”

Rodriguez Lima has no plans to leave the office of immigrant affairs, but in a strange way, she hopes that one day it will leave her.

“Ideally, agencies have all the tools to serve immigrants,” she says. “Ideally, we wouldn’t exist because people are thinking about this population. But that’s not the case. They’re often an afterthought.”

Not to Catalina Rodriguez Lima.