Learning by Real-World Discovery Inspires Generations

Hands-on science education and research is one of TU’s founding principles.

Words By Megan Bradshaw

Photos by Alexander Wright ’18 and Lauren Castellana ’13, ’23

Video by Henry Basta ’11 and Ron Santana ’98

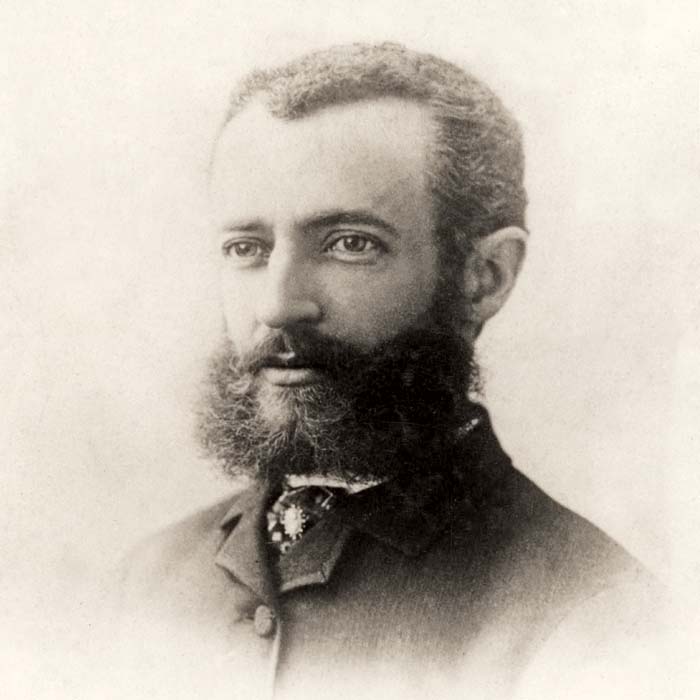

When the Maryland State Normal School (MSNS) opened in 1867, it offered instruction in botany and hired a lecturer to teach natural

history. Four years later, the school now known as Towson University made another

key hire: George La Tour Smith.

Smith became MSNS’s first dedicated physics, chemistry and natural history professor. A botanist and keen photographer when the skill was considered a science, he came to the school from the U.S. Coast Survey, where he constructed and mapped lighthouses for the organization.

From its inception, excellence in hands-on experiences and science education have been bound together in TU’s curriculum and mission. Today, the university continues Smith’s legacy as the oldest and largest preparer of educators in Maryland and an institution on its way to a Carnegie Classification of R2, signaling high research activity.

“One of the things that attracted me about Towson was that it emphasized undergraduate research,” says TU emeritus biology professor Rich Seigel. “That was one of the things Towson has always prided itself on—training undergraduate students—and there's always been financial support, logistical support, credit for doing the work. If you want to learn about doing undergraduate research, this is a good place to be.”

Seigel calls his own undergraduate research experience “the single-most important thing that I ever did” and describes research as addictive.

“It tends to take over your life, to give you a very different perspective on things,” he says. “[When I was in school,] I was out in the field with another undergraduate student studying turtle nesting one afternoon when she said, ‘Don't you have an organic chemistry final today?’ I said, ‘Yeah, why?’ She said, ‘Rich, you're going to miss your final.’ I said, ‘I'll take a makeup. There’s too many turtles nesting for me to worry about a final.’ I will not, to this day, accept a master’s student in my research lab who has not done undergraduate research experience.”

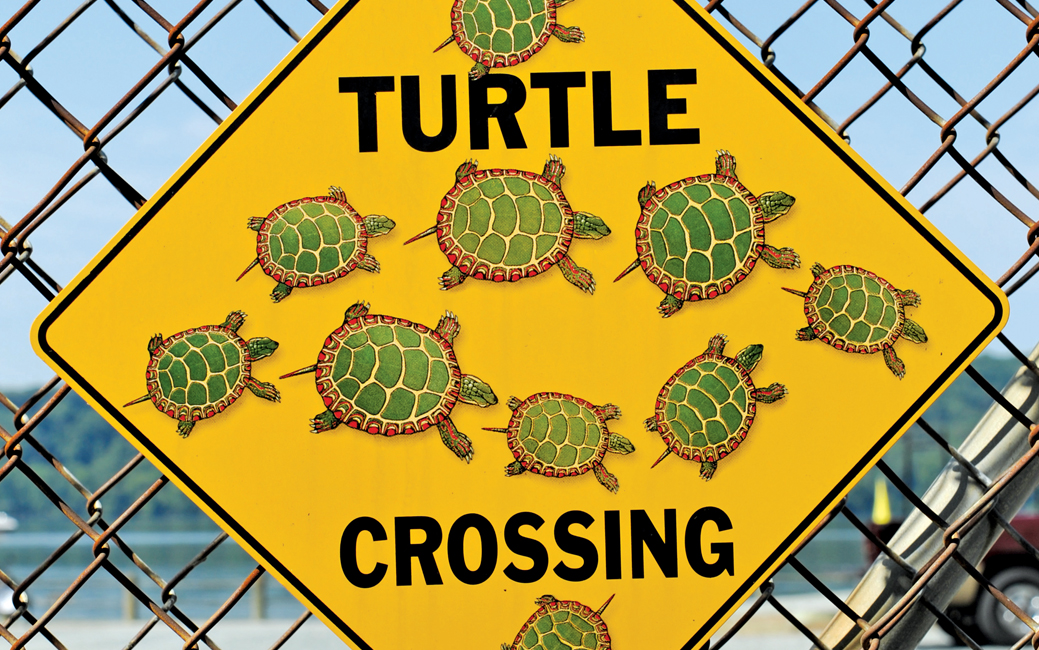

A small contract with Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources in 2008 to verify the existence of the endangered northern map turtle in Cecil County ballooned into a long-running research project for Seigel and his students—graduate and undergraduate.

Working in partnership with the town of Port Deposit, Seigel and faculty colleague Steve Kimble are based out of a field station tucked behind a marina. There is a narrow, 30-foot beach in front of the field station where the endangered turtles come to lay eggs.

A larger contract with the state has allowed the research team to expand its scope, and town officials have responded positively, even adopting the turtle as a town

mascot. The initiative was recognized in November 2022 with a BTU Partnership Award, which recognizes faculty, staff, students and community organizations engaging in

exemplary partnerships that

embody the spirit of TU and benefit the communities they serve.

“It’s worked out great for everybody, the town, students and professors at Towson and the turtles,” says Kimble, a clinical assistant biology professor.

There are many avenues for TU students to pursue research at undergraduate and graduate levels. TU generated nearly $9 million on research in 2021–22 and received $15 million in external funding the same year. Students can contact the Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Inquiry and the Office of Undergraduate Research, which connects them with faculty who need help conducting their research. Or they can reach out to their professors on their own.

Jenna Cole ’15 was one of those students.

She took Seigel’s herpetology course and approached him after class one day. Cole shared her experience volunteering in her hometown with diamondback terrapins, and Seigel invited her to visit the project in Port Deposit.

After volunteering with him, she became a student worker on the project until Cole earned her bachelor’s degree in biology with a focus on organismal biology and ecology and moved to Florida for graduate school.

She started with nesting surveys, creating artificial nesting plots to see if the turtles had a preference in soil. Cole also sat in a deer blind for hours-long shifts to observe the turtles climbing onto the beach: where they went, what they investigated and where they nested. Then she would mark the nests for continued monitoring. Any hatchlings they caught were marked for identification with orange paint.

Cole and her fellow student researchers also tested whether turtles would accept artificial basking surfaces. Because of the Conowingo Dam upriver, the water levels changed and could submerge the turtles’ preferred basking areas. So, they built wooden platforms that raised and lowered with the water but were anchored to the riverbed.

“We wanted to see if they would actually use it,” Cole says. “The answer was yes, after a little period of adjustment when they weren’t sure what was in the water with them. It seemed like if we invested in some of these floating platforms and maintaining them, the turtles will use them and benefit from them.

“My experience working at Towson and working with Rich really set me up to understand what was important to me as a student and where I wanted to go with my career,” says Cole, who finished her master’s degree at the University of Florida. “I learned I like the field work; I like working hands on with the animals more so than working in an office all day every day.”

These are all skills she draws on now as a wildlife biologist for UF, doing reptile surveys and invasive reptile removal.

She says the experience she gained collaborating with professionals and the community of Port Deposit has been beneficial to her in her new role.

“I need to use that skill in outreach here. I’m not working with cute turtles anymore. I’m working with snakes and lizards. And people don’t have the same opinions of them as they do the turtles. So learning how to communicate professionally, politely and understand what’s important to the community members really helped me do what I do now.”

TU’s Center for STEM Excellence in downtown Baltimore also is entirely community focused. It supports Maryland’s elementary through high school learners in three ways: with a dedicated lab, as a field trip destination and as a resource center for teachers through equipment loans and professional development.

Students from every county in the state have participated in programming through the

center, a three-hour experience where they are presented with a question, gather data,

analyze

it and develop a conclusion.

“Lately, our focus is on social justice in science because my team and I feel strongly these issues are real to the students we serve,” says Mary Stapleton, center director. “We’re able to bring students into science who might not otherwise have seen the relevancy to their lives.

“Equity of access is a big thing with us. We want to make sure all students have access to high-quality student programming, whether it’s the curriculum, materials or trained teachers.”

In 2022, the center served more than 18,000 students through field trip experiences and equipment loan programs.

Stapleton and her team have worked hard the last few years to include more elementary programming to a slate that had been middle and high school heavy.

“Elementary is an interesting challenge because the teachers teach everything, for the most part, and a lot of elementary teachers are not science majors,” she says. “Many don’t have science backgrounds and can be intimidated to teach it.

“That's where we can make a huge impact, providing these teachers with the support for their own content knowledge as well as materials that are easy to use, that they can quickly fit into the 20 minutes once a week that they may have for science.”

George La Tour Smith was the secretary of Cornell’s Engineering Society as a senior; in 1870, the alumni association listed

his occupation as civil engineer. Whilehe had extensive training in various scientific

fields, he faced a learning curve when it came to teaching.

As former MSNS principal Sarah Richmond remembered in 1893, “His pupils were the graduating class. Hitherto their instruction had been given by the Principal only. The class rather resented the change and I suspect there was an inward feeling of satisfaction when an experiment of the new teacher’s failed in the promised effect.”

Smith recognized he needed more experience, so he spent nights in the school laboratory, studying just as much as the students he taught during the day.

That commitment paid off almost immediately.

Minnie Davis (Class of 1887) wrote of Smith in 75 Years of Teacher Education: “It is not possible that any teacher could ever be more beloved than was Professor George Smith. Not only was he a truly great instructor, but there was never anyone who found more real joy in teaching. He made his pupils feel that he was benefited, not they; that they conferred a favor upon him when they asked for help.”

Smith took his botany classes to Druid Hill Park to study plants and their natural habitats. Even then, science educators prized hands-on activity as a learning method.

Current biology professor Sarah Haines was greatly influenced by her undergraduate research experience and includes the same technique in her courses.

“Pretty much all of my courses have some kind of hands-on, outdoor field component to them,” she says. “We go outdoors in the Glen on campus where the students are collecting data or using equipment.”

Another activity her education majors complete is something she calls life in a square meter.

“They have a PVC pipe that's shaped in a square,” she says. “And they lay that down somewhere in the open meadow area of the Glen and do vegetation samples. They look for things that are crawling on the ground or sometimes we even find animal droppings.

“Then I might say, ‘OK, how could you do this activity with your students because it's perfectly appropriate for elementary or middle level?’ We pick it apart: we look at the pedagogy, the teaching theory behind it. It's like content and teaching methods put together in one course.”

Haines also runs a summer study abroad program in Costa Rica. Senior Bailey Hardwick participated last year.

“It taught me so much about ecology, ecosystem interactions and the effects of anthropogenic climate change,” she says. “Costa Rica is a great example of what a country can do for the environment and use it as a resource without exploiting it. Seeing that in person versus learning about it in a classroom was so beneficial.”

The environmental science and studies major has done internships with Harford County Parks and Rec, Eden Mill Nature Center and Marshy Point Nature Center.

“My internships focus on environmental education and interacting with the public,” says Hardwick. “I realized that's the path I want to go down. Because then I can work in my interest of ecology and conservation and tell the public all about it. I know from the research I did that educating people is the best way to get them to care about the environment. I'm still able to enact the change I want to see, just in a more indirect way.”

Pam Lottero-Perdue, a science and engineering education professor in the Department of Physics, Astronomy & Geosciences, thinks of her classes as stories, with topical threads linking course content and her students’ backgrounds.

“I want it to make sense. I want it to be connected to their lived experiences, to what they might teach, and to itself: adhesion and cohesion,” she says.

In fall 2021, Lottero-Perdue took special education and elementary education majors in her earth-space science class to the Conowingo Dam in Harford County, near the TU in Northeastern Maryland building where she taught the class.

Her students brainstormed the questions they had about the dam and spent the rest of the term answering them. Lottero-Perdue’s students learned about erosion, connected the dam’s technology with ideas about engineering that are part of the Next Generation Science Standards teachers must adhere to and studied the structure’s history and the equity issues that faced the dam’s construction workers.

Then they visited the site as well as the old town of Conowingo that was submerged for the dam to be built. Lottero-Perdue’s course touched on these topics throughout the rest of the term.

Her methods have struck a chord with her students. Katie DePew ’18 was a career-changing, mature student who took courses with Lottero-Perdue.

“Dr. Lottero had hands down the biggest impact on me throughout my time at Towson.

She pushed me to be a better student every single class,” she says. “My very first

student-teaching

experience was in a fourth-grade classroom for science. We would learn the material

with Dr. Lottero and then teach it to the fourth-grade group. I absolutely loved the

way the learning and the teaching aligned. Dr. Lottero would excitedly teach us the

content, which we would then be equally as excited to teach to the fourth graders.”

Smith’s teaching skills went beyond the camera and the classroom. For a short while, he took over drawing instructor

duties at MSNS—possibly even teaching students how to draw

botanical specimens. He was instrumental in the school’s Arbor Day festivities.

He was also a member of the Botany Club of Baltimore and secretary for the Photographic Society of Baltimore. Smith was a member and curator for the Maryland Academy of Sciences, the precursor to the Maryland Science Center. His ability to transfer his scientific skills into other areas of his life helped him make a positive impact on the Baltimore-area scientific community, outside of public education.

Scientific education through outreach is still a key component to TU’s curriculum.

Thomas Potter ’22 was working as a naturalist at the Wilde Center in upstate New York doing public education before enrolling at TU as an environmental studies major with a concentration in informal science education. He is now in TU’s master’s program for geography and environmental planning and hopes to enroll in the new sustainability doctoral program in the future.

“Where I want to end up with these degrees is somewhere I can give communities the

information and tools they need to advocate for themselves, like a community organization

or

nonprofit,” Potter says. “I want to connect the intersecting facets within any given

system—politics, science, economics—and turn that into a narrative that informs individuals

about the facts of a situation, why they should care about it and what they can do.”

A similar motivation drives Gia Grein ’10, the lead specialist with the wildlife conservation team at the World Wildlife Fund. Her team looks for solutions to the illegal wildlife trade.

The environmental science and studies major took courses with Haines and appreciated her approach.

“It was very hands on in taking something that everybody loves—nature and the outside—and diving deeper, looking into bigger issues like climate change and all its implications. It made what we were learning more tangible,” Grein says.

She sees a direct correlation between what she learned in those classes and what she does now.

“I work with private sector companies to help them understand what the illegal wildlife

trade is and help them find solutions,” Grein says. “I want to take these same skills

of making these crazy, difficult global issues more digestible, easy to understand

and offer solutions.

Instead of talking to kids, I'm talking to businesses.”

Jonathan Wood ’11—a former history major—does spend his days talking to kids. The historical park manager at the Benjamin

Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Catonsville, Maryland, works outdoors—his favorite

office—maintaining trails, the orchard and garden beds and facilitating programs and

events the park runs. One is a program for 2-to-5-year-olds offering an early childhood

immersion into nature through hands-on activities.

“Mr. Benjamin Banneker was a model for self-teaching with hands-on experiences,” Wood

says. “When he had the opportunity, which was limited as a Black man in the 18th century,

he took [it] and ran with it. He’s very well known now as the first Black man of science

in the Americas. And it was all hands-on experience that he used to teach himself.”

Over the course of the northern map turtle project, around 30 students have been trained in research and/or scientific communication and outreach.

TU’s research station is in a renovated gas house. Downstairs is a town museum, and upstairs there are quarters in the back for students to stay if need be and an area in the front to communicate with tourists and school children about the turtles and conservation.

“This outreach arrangement has been great for Towson University interns we hire in

the spring

who are interested in scientific communication,” says Kimble. “They go up there on

Saturdays and Sundays during the summer, and they have all kinds of other stuff they

can teach visitors about: how we track the turtles, the shells and why they’re called

map turtles. And sometimes, if we’re lucky, they can see little hatchlings headed

back to the water.

“Sometimes it’s two people, and sometimes it’s 30,” Kimble adds.“If you do that all summer, year after year, then you can reach hundreds of people. The outreach program has the potential and is already touching lots of lives: turtle lives, lives of people who are in the area and lives of the Towson University faculty and students.”

In 1965, university officials decided to name the newly erected science building on campus George L. Smith Hall, in honor of his many academic and scientific contributions. In 2021, TU built the state-of-the-art, 320,000-square-foot Science Complex. With its 50 teaching laboratories, 30 research laboratories, 50 classrooms, eight lecture halls, 10 collaborative student spaces, an outdoor classroom leading to the Glen Arboretum, a rooftop greenhouse complex, a new planetarium and an observatory, TU is better positioned than ever to continue to honor its commitment to science education and research.

In 1892, Smith’s last year at MSNS, there were 331 students enrolled in the entire

school. As

of spring 2022, the Fisher College of Science & Mathematics alone had 3,305 students enrolled, based on their first majors. Looking at how far

Towson University has come, George La Tour Smith surely would be impressed.