Feature

A warrior for the wounded

Jenna Link ’07 puts her heart and soul into advocating for those who are injured serving their country.

It’s only Tuesday, but Jenna Link ’07 already has had a hell of a week. It started yesterday with her standard 6 a.m. Monday call, during which she learned of all casualties, significant injuries and illnesses of active U.S. Navy personnel in the past week. Later that day, she attended a meeting at the Pentagon during which eligibility for the Gold Star Program, which provides services and support to the families of armed forces personnel who die on active duty, was debated.

Today, Sept. 30, the Washington Commanders’ Jayden Daniels was supposed to be at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda to visit with members of the Navy Wounded Warrior Program, which helps sailors and Coast Guardsmen with injuries—physical or psychological—with their non-medical care needs. But the star quarterback sprained his knee a few weeks earlier and had to reschedule.

So now Link, 41, who leads both programs for the Navy, is dealing with myriad scenarios that could arise if a potential government shutdown becomes a reality at midnight. (Spoiler alert: It did.) Despite all that, she manages to focus on what she says is the most important part of her job: the people she and the programs she runs serve.

“You’re dealing with people who are going through the most traumatic times of their lives,” she says. “It’s going to be challenging, so you have to learn to deal with these situations on the fly and handle them the best you can. I charge my team with operating in the above and beyond, always encouraging them to go that extra mile for our [people]. How can we help? How can we make it better?”

Lately, she’s been answering that question by implementing support groups for families of service members who lost their lives to suicide. Of the more than 200 deaths annually among active Navy personnel, Link says approximately half are due to suicide. Currently, of the roughly 8,700 survivors the Navy Gold Star Program manages, 2,100 have lost their loved one to suicide.

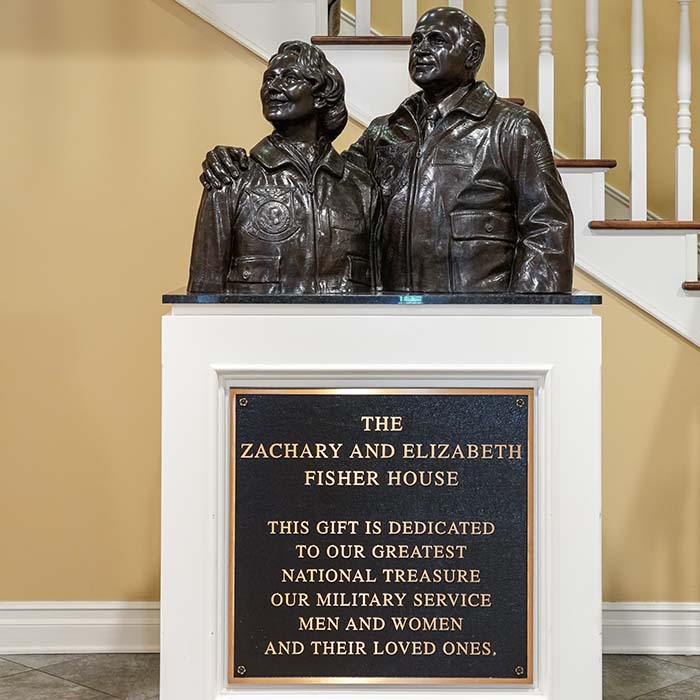

She’s discussing all this with empathy, anguish—and a little stress—in her voice outside one of Walter Reed’s five Fisher Houses. The facilities, each of which have private bedrooms and bathrooms and a common kitchen, laundry room, dining room and living room, are funded by a private foundation and provide a free place for the families of active-duty service members and veterans to stay while their loved one undergoes medical treatment or rehabilitation. They’re one part of countless ways that Link and the programs she manages lend a helping hand.

“She’s very smart, and she listens,” says Michael Ybarra, who was general manager of Walter Reed’s Fisher Houses until he retired in October. “We know—and everyone who stays here knows—that she cares.”

Link's early life

Link proudly describes herself as an Air Force brat. Her father, Walt, served in both the Navy and the Air Force. She grew up on military bases in places like Millington, Tennessee; San Antonio and Las Vegas before the family settled in Maryland when she was in fourth grade. Her naturally outgoing and caring manner, which would come to serve her so well in her professional life, paid off in her childhood as well; unlike many kids in military families, she relished moving frequently and making new friends.

After earning her associate degree, she followed a friend to TU, where she majored in business administration with a concentration in marketing. She studied abroad in Panama and says that she enjoyed her TU experience.

I charge my team with operating in the above and beyond, always encouraging them to go that extra mile for our [people]. How can we help? How can we make it better?

Jenna Link

“The business communications, strategic planning, those kinds of courses were huge in what I’m doing today,” she says. “I'm briefing three- and four-star admirals regularly, sometimes with just moments notice. My education was instrumental in my ability and confidence to perform my job.”

During and after college Link worked full-time for the clothing company Aeropostale. She rose through the management ranks, landing a general store manager position before joining a defense contractor, which led to her career with the Navy.

Heading Casualty Support Programs

After a dozen years in various roles, in 2022 she was charged with running the Casualty Support Programs branch at Commander, Navy Installation Command, overseeing the Navy’s Wounded Warrior, Gold Star and Fisher House programs. For the wife of a disabled veteran, the job is intensely personal.

I have sympathy, but I've seen a lot of incredible success stories. You may be disabled, but you're still able. You're still able to do so many things.

Jenna Link

Her husband, Nathan, was injured during a deployment in Iraq. He also suffers from PTSD and a litany of other maladies from his time in the U.S. Army. He credits his wife’s positivity, charisma and leadership for helping him navigate the system when he returned home.

“She is my rock,” he says. “In my mind I thought, ‘I’ve got all my limbs; I’m not in a wheelchair.’ So I didn’t think there was anything wrong. But she knew that I definitely needed some help.”

Seeing her husband fight through his issues—some days are better than others—motivates Link.

“I constantly want to do more,” she says. “I have sympathy, but I've seen a lot of incredible success stories. You may be disabled, but you're still able. You're still able to do so many things.”

The Navy Wounded Warrior Program

The Navy Gold Star Program was established in 2014 and charged with providing long-term support to families of sailors who die on active duty. It works with the spouse, children, parents and siblings of the deceased service members to connect survivors to each other, offer counseling, financial planning, employment assistance and many other services.

Six years earlier, Congress mandated the creation of the Navy Wounded Warrior program as a way for the branch to manage the non-medical care of seriously wounded, ill or injured sailors and Coast Guardsmen. It offers them a tailored plan to enhance their recovery and ensure they are prepared for their likely transition to civilian life.

“Service members enrolled in the program have serious illnesses and/or injuries and are very unlikely to return to full duty, so we focus on successfully transitioning them,” Link says. “Whether that’s working on their resumes, setting new career goals, offering financial planning assistance, we make sure that their new normal, whatever that may look like for them, is set up should they medically retire from the Navy.”

There are about 900 active-duty sailors and Coast Guardsman in the program for reasons including combat injuries, mishaps aboard a ship, cancer, motor vehicle accidents—you name it. Each week the program reviews about 40 new cases.

The Warrior Games

Kayla Saska became one of those cases six years ago. While deployed in Japan, she suffered traumatic brain injury and hurt her back and lower extremities while fixing missile radar equipment aboard the USS McCampbell. She underwent numerous surgeries at Walter Reed from 2022 to 2025.

“If I didn't encounter Wounded Warriors when I did, I would be really lost,” says Saska, 27. “I had no family or friends in the area. They were able to help get my family to the area. For every surgery, they were able to help me get a little bit of responsibility off my shoulders and made the focus just about me and the mission of getting better.”

When people say that [the Wounded Warrior Program] saves lives, they’re not joking.

Kayla Saska

During her recovery, Saska began participating in the Warrior Games, an adaptive sport competition for disabled veterans. She’s competed in wheelchair rugby, basketball, archery, shooting and field events. The competition has impacted her in fundamental ways.

“When people say that [the Wounded Warrior Program] saves lives, they’re not joking,” she says. “It truly changed my life by giving me a different outlook. You go from what your normal was to what your normal is and you make the most of it.”

It certainly changed Travis Wyatt’s life. In July 2020, he was injured in the USS Bonhomme Richard fire in San Diego while across a pier onboard the USS Fitzgerald. Wyatt, whose nickname is JIGSAW—his call sign for his 13 years in the Navy—suffered blast trauma to his head, chest, back and brain.

After the incident, he was lost in limited duty status until, he says, adaptive sports with the program showed him a new way forward. He met Link at the 2022 Warrior Games, at which he competed in archery, precision air rifle, swimming and cycling.

“Any warrior that gets the chance to talk to her, she 100% focuses on that warrior,” he says. “She is not thinking about something else. She’s interested in hearing what you have to say about what's good, what's bad and how it could be better.”

It created a path for me to keep living instead of surviving.

Travis Wyatt

Wyatt, 44, a married father of two, struggled with depression and anxiety that he says may have overtaken him had it not been for his recovery care coordinator and team at the Navy Wounded Warrior Program.

“I'm forever in their debt because they actually care about helping injured service members recover and find that, yes, our careers may end, but there's other stuff that can keep us active,” he says. “It created a path for me to keep living instead of surviving.”