Feature

Elevating Voices

TU’s Unearthing Towson’s History Project aims to enrich the university’s present and future by seeking the voices of those missing from its past.

It started with one thought: Why don’t we teach more of TU’s history to the students?

History professor Christian Koot, in the College of Liberal Arts, remembers this as a jumping off point for Unearthing Towson’s History, a project that has grown to include:

- 14 student researchers and several members of faculty and staff

- a database of nearly 1,400 articles, photos and ephemera

- 17 oral histories of faculty, staff and alumni from the last 60 years.

“The previous university archivist and I started talking about it at the 150th anniversary (of the university) in 2016,” says Koot. “I thought a TSEM (a seminar-style class) might be the vehicle to do that. When Ashley started here in 2016, I had half a syllabus. I dragooned her into working with me.”

We began to realize there was a part of that story that we could and needed to tell as well.

Christian Koot, chair in the Department of History

Ashley Todd-Diaz, assistant university librarian for special collections and university archives, had had a similar thought to Koot’s. She and Brian Jara, director of inclusive excellence education and support, had started searching the university’s archives to see how Jara and his colleagues could use them as an internal educational tool.

“The project also grew from the larger national movement of institutions beginning to investigate their origins and histories,” Koot says. “We began to realize there was a part of that story that we could and needed to tell as well.”

Connecting with TU’s historical figures

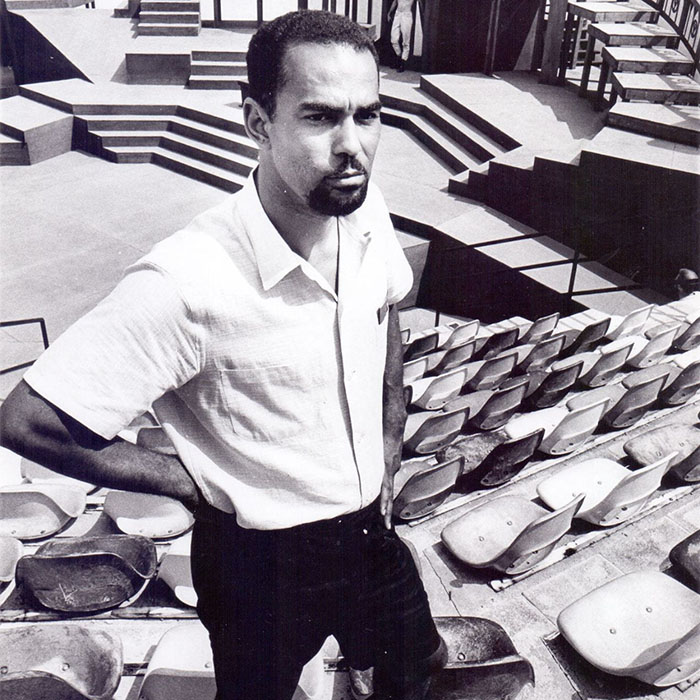

Julius Chapman came to TU in 1969 as the first dean of minority affairs. When he arrived, Black enrollment was less than 1% of the student population.

During his tenure he recruited and mentored Black students while playing a pivotal role in establishing the Black Student Union, the Black Faculty and Administrators Association and the Black Cultural Center. He also brought historically Black Greek Life organizations to campus. In 2021, TU dedicated a section of campus and placed a bust of him in the Chapman Quad to honor him and inspire passing community members.

The oral history arm of the project began with Chapman in late 2019. But just as the cameras started rolling, an historic event froze time: the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It was meant to be a preparatory oral history,” Todd-Diaz says. “We visited him at his home and got to know him a little bit, asked him some questions. Our plan was that the following semester in 2020, we were going to have students conduct the official oral history and film it.”

When students, faculty and staff returned to campus after pandemic restrictions eased, the TSEM and archival research coordinated more closely, and the project gained steam.

A bust of Julius Chapman in the Chapman Quad, dedicated in 2021. Chapman was TU’s first dean of minority affairs. (Photo: Lauren Castellana '13, '23)

An interdisciplinary effort

Koot and Todd-Diaz’s TSEM, Towson University Students in the Upheaval of the 20th Century, tasks students with an original research project on something about the history of TU or its students.

To do that, they use the university archives. But as students either followed their own interests or the suggestions of Koot and Todd-Diaz, they began to see tremendous holes in the archival collection such as the experiences of Black students, disabled students, LGBTQ students and individuals at those intersections.

“The oral histories are designed to fill those gaps in the archive and then for the students to use,” Koot says. “One of the results of the project is creating a bigger corpus of information that the students can interact with and use in their projects.”

Researchers turn detectives

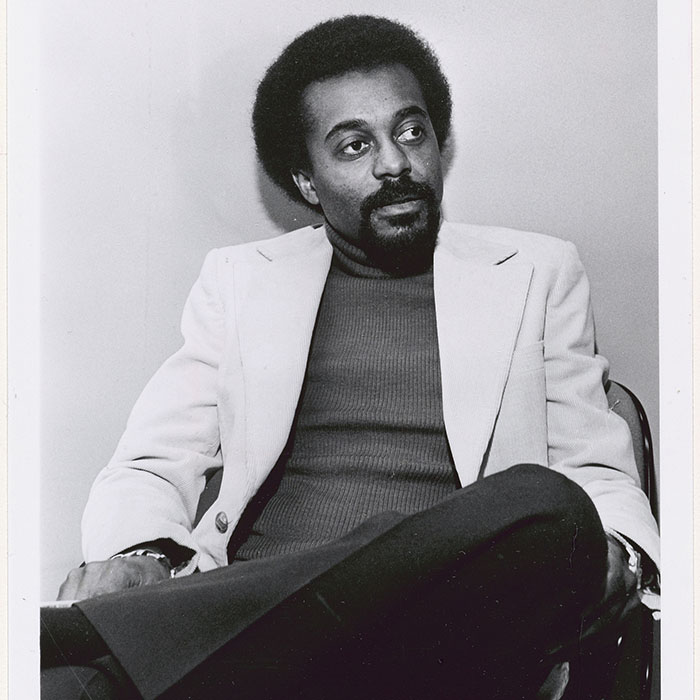

Whitney LeBlanc was the first Black faculty member hired at TU. He came to the university in 1965 at the urging of theatre department chair Dick Gillespie.

LeBlanc taught for five years—during which a group of KKK extremists unsuccessfully rallied on campus to shut down his production of “And People All Around”—before he left to create the ground-breaking TV show “Our Street” and advise for the 1970s sitcom “Good Times.”

Todd-Diaz credits the student researchers’ tenacity and ingenuity in uncovering individuals for oral histories.

“One of our researchers found [LeBlanc’s] personal website and asked me, ‘Can I email him?’ He wrote back that night,” Todd-Diaz says. “It’s eye-opening for students to see that they can make these connections within their broader community. It’s a connection that wouldn’t have existed if they hadn’t taken that step.”

Allie Lawrence ’21, who majored in history while at TU, was that researcher.

“If you go back and watch my interview with Mr. LeBlanc, I was close to tears for most of it,” she says. “The horrendous stuff he had been through saddened me. I asked him, ‘Were you scared?’ He said no. I was shocked because I was scared for him. But he just had this courage that not a lot of people have.”

It’s eye-opening for students to see that they can make these connections within their broader community. It’s a connection that wouldn’t have existed if they hadn’t taken that step.

Ashley Todd-Diaz, assistant university librarian for special collections and university archives

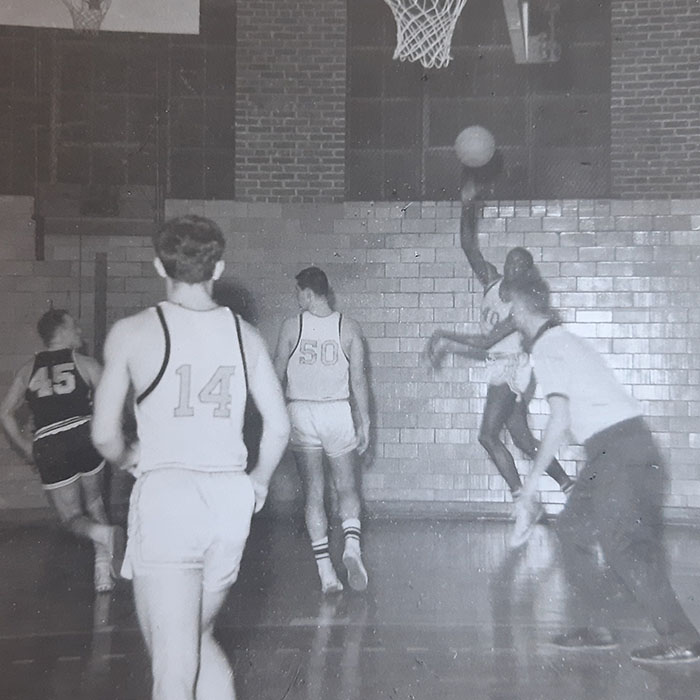

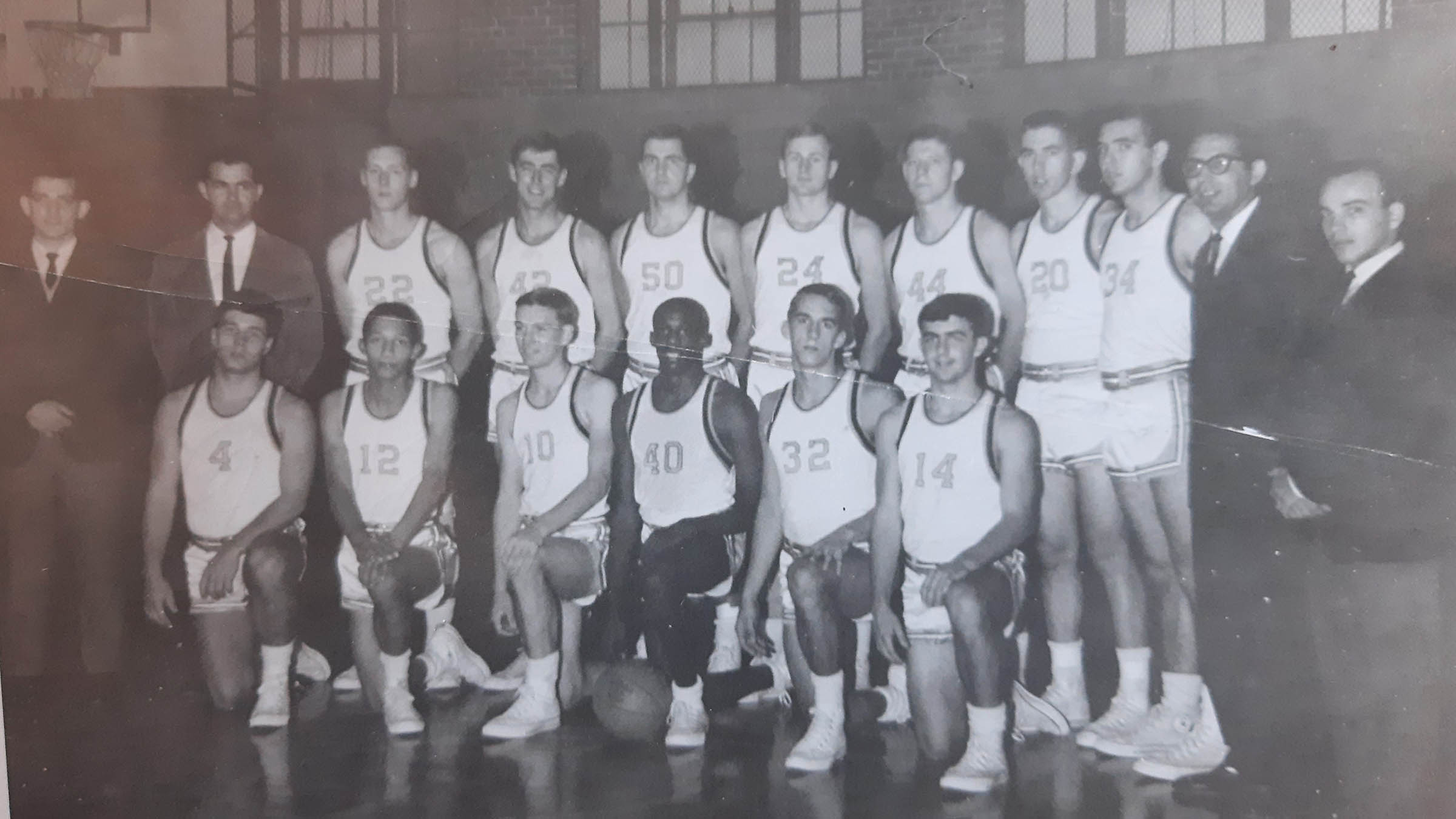

Another oral history that came from student curiosity was James Newton’s. He was one of TU’s first Black basketball players. In a moment of serendipity, Newton spoke about his view on the KKK protest at LeBlanc’s production.

“Our researcher’s response on hearing James talk about this as a student who hadn’t come face-to-face with so much hatred before, her question was, ‘Well, what did the university do to support you in that moment? Were there counseling services?’ And he was like, ‘No,’” says Todd-Diaz. “It’s so important for students to see from another perspective just how different the campus was and what it was like for students who were going through these incredibly traumatic experiences, essentially, on their own.”

This past fall, several TSEM students used that interview in their papers, something they couldn’t have done just a few years ago.

James Newton (#40) was one of TU’s first Black basketball players. He is pictured here shooting a ball (left) and then with his team in a group photo (right). (Photos courtesy of TU Athletics)

Including many voices

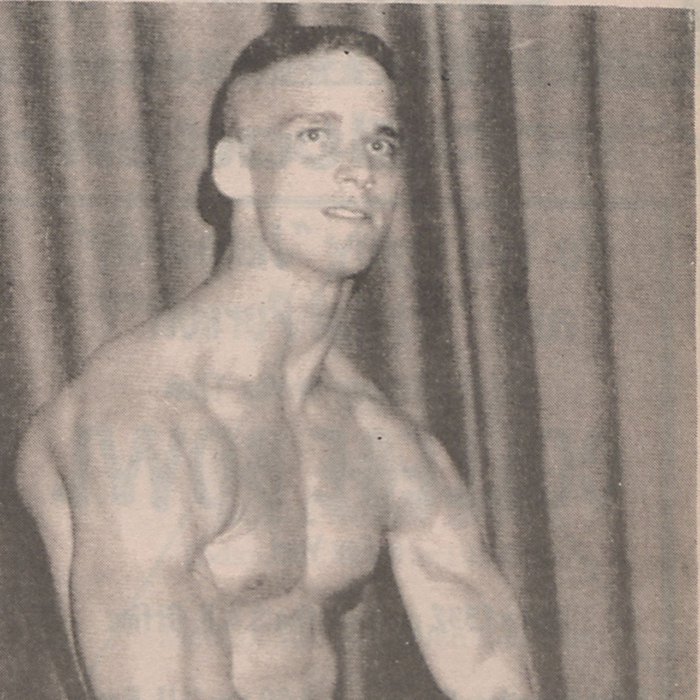

Arnie Slater ’93 attended TU after the Americans with Disabilities Act—the world’s most comprehensive civil rights legislation for people with disabilities—was passed in 1990. In his oral history, he recalls living on the 12th floor of a dorm, despite having cerebral palsy, and needing to change his major right before he graduated because of hiring prejudices in his chosen field of occupational therapy.

“One of our student researchers a couple summers ago asked, ‘What’s the history of [Accessibility and Disability Services] at TU?’ And we realized nobody knows,” Koot says. “She did a couple of oral histories of an early director (Lonnie McNew) and a disabled student (Slater). We had a TSEM student then this fall write a paper about that topic too.”

Bethany Firebaugh ’24 interviewed Slater. Through the experience, she ended up building an entire online exhibit on the history of accessibility and disability services at the university.

“When I was in undergrad, I was still trying to figure out exactly what career path I wanted to take,” she says. “I’m currently at the University of Maryland–College Park, getting my master’s in library science with a specialization in archives and digital curation. This project really made me fall in love with archival science.”

It had the same effect on Lawrence. She also earned her master’s at UMD and is now a public librarian in Anne Arundel County.

“I really love archives,” she says. “But what I loved about Unearthing Towson’s History is that ability to help someone through an oral history or to share their story—that meant so much to me. It wasn’t so much about the records but the stories and the people that you could impact with them.”

While Koot and Todd-Diaz are co-teaching a class this fall about archival practice and theory as well as history and historical theory and oral history as methodology, the pair will also focus on practical skills.

“They’re going to learn how to ask good questions, how to frame those questions,” Koot says. “They’re learning the soft skills of sitting across from someone: How do you get someone to open up and share? How do you guide that conversation?”

Listen to selected recorded oral histories

Linda Morris ’69 is one of the alumni Lawrence spoke with for an oral history. Morris was impressed.

“She was very good. She was well prepared,” Morris says. “She had very insightful questions that I might not have thought to ask. I didn’t have any good feelings about Towson before I did this interview, and (the oral history) made me feel better about Towson because it was as though someone cared about capturing the true story. It’s important to have everyone speak from their perspective. Because it’s like a puzzle…everybody has a piece of the puzzle, and it’s good to hear it so you can put it together.”

Just as national conversations 10 years ago helped bring this project into existence, in 2025 they have swung in the opposite direction. So what should Koot and Todd-Diaz do?

One of the things I’ve always been interested in is how powerful small stories and the experience of individuals can be.

Christian Koot, in the College of Liberal Arts

“I think the people that don’t want it done are not a majority, particularly of our community,” Koot says. “In some ways, it’s even more vital. One of the things I’ve always been interested in is how powerful small stories and the experience of individuals can be. What’s happening on a national or global stage isn’t everything; what’s happened right here is an important story to tell too.”

According to Koot, students in the fall TSEM recognized that the current moment is one of historical significance.

“One of the successes of the class is cluing students in that when they think about these big moments in the past, those are experienced by lots of people in small ways, like the people that came before them at Towson,” he says. “So their experiences are part of that bigger story too.”

Just what’s in the archives?

Todd-Diaz talks to the students about how the materials in the archives are the unpublished ephemera that people likely weren’t expecting to be read broadly: their diaries or letters, photographs, items that reflect everyday life.

“We talk about the fact that if materials [about the founding of the Black Student Union] hadn’t been maintained at TU, they may be in someone’s attic right now or they would have been thrown out,” she says. “But because they’re here and we can study them, suddenly we have this very interesting view into a sequence of events in 1969 and 1970.”

...we also need to be doing a better job as a campus of thinking about our history and what is being kept.

Ashley Todd-Diaz, Special Collections and University Archives

Todd-Diaz stressed that the staff in Special Collections and University Archives welcome all types of material submissions.

“As the archives was being founded [in the 1970s], there was a big push to send things to the archives,” she says. “But we have almost nothing from 2000 on. Part of that is we switched to digital records, and people aren’t thinking about sending things to the archives.

“It’s a broader conversation that we’re teaching our students, but we also need to be doing a better job as a campus of thinking about our history and what is being kept so that there are those records in the future.”

Inspiring future Tigers

One of the ideas behind the overall project is creating a sense of belonging for students who may not see themselves reflected in the current history as it’s represented in larger narratives, the website or the archives.

Koot and Todd-Diaz hope this project continues as a venue for students learning about the history of TU as well as practicing the skills of being scholars who continue to ask questions.

“Seeing our students’ dedication to this project is amazing,” says Todd-Diaz. “But then also to see current students using the collection, alumni and past faculty contributing and the administration’s willingness to grapple with owning our history is significant.”

Be a part of TU history

Special Collections and University Archives is seeking meeting minutes, policies, flyers, photographs—anything relating to TU events and experiences. The archives are meant to document TU’s operations, from the university level right down to individual students, so they are requesting submissions from faculty, staff, alumni and students.

Connect with Special Collections and University ArchivesKoot and Todd-Diaz think there’s a lot of opportunity within Unearthing Towson’s History to showcase all the individuals who are part of the TU community.

“I’ve always very firmly believed that everyone deserves to look at the historical record and see some part within it that they can relate to,” Firebaugh says. “Coming into this archival silence in regard to accessibility and disability services has really made me want to dive more into this work.”

It’s very clear Firebaugh, Lawrence and current researcher Abigail Bowling ’25 have understood the assignment.

“It is important to make sure all the voices that have shaped Towson’s history are represented in our archive and in our historical presentations,” Bowling says. “There’s a lot of individuals who have had a bigger impact than maybe they themselves even realize. It’s important that we continue to highlight those stories, and there is a certain comfort in knowing that we have this history to learn from, we have these people to learn from and they’re not lost to time.”

In their own words

Liberal arts alumnus

Arnie Slater ’93

“I was in Tower C, and I think there were 12 floors. During fire drills or whatever I was forced to go down 12 flights of stairs, which I thought was like, ‘Somebody didn’t think this out very well.’ But I was young. I didn’t complain. I just figured out a way to get down the stairs really fast: I grabbed either side of the railings down the stairs and slid down. Luckily, I never fell or hurt anybody. But I should never have been put on the 12th floor.”

first Black professor at TU

Whitney LeBlanc

“The production of ‘And People All Around’ was much more powerful than I anticipated. It was a play based on the killing of the three civil rights workers by the Klan in Mississippi. I had no knowledge of opposition to the play by the Klan until Dr. Hawkins (then-university president) called (theatre chair) Dr. Gillespie and myself to his office the day before the play was supposed to open and introduced us to two FBI people from Washington, D.C., who had gotten information that the Klan was preparing a protest to close down the production. Dr. Hawkins wanted to know what our response was. I said, ‘Well, let them come. They’re welcome to see the play.’ Dick Gillespie and Dr. Hawkins agreed with me, and the FBI said, ‘Well, it’s not that simple. We have to take some precautions.’ They assigned a particular agent to me and the students in the production. About 20 Klan members came in full regalia and protested on York Road.”

Liberal arts alumna

Linda Morris ’69

“When I went back to school (after the King riots), I was in Dr. Toland’s sociology class, and he was asking students how they felt. This one guy started talking about how, ‘Oh, we give them (talking about Black people) training, we give them this, we give them that and they do this to us?’ I just couldn’t sit there anymore. I stood up and said, ‘Well, we don’t want you to give us a damn thing. We just want what is rightfully ours.’ He became an administrative judge for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. I worked for them too, and I really thought about what he had said that day, and I could not reconcile the fact that this person who said these things became an administrative judge to adjudicate discrimination complaints.”

Men’s basketball player

James Newton ’68

“I can’t remember negative experiences. I can remember on the road with the team. We would travel to Virginia, and we would travel to the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The team would stop for a meal, either going or coming home from a game. I remember the coach would get off the bus and go into the restaurant to find out if a Black person could eat there, and if the answer was ‘No,’ we would find another place to eat. The guys on the team were very frank, and their reaction could have been, ‘Oh, we’re bringing Newt’s meal out to the bus. Let’s go eat.’ But there was none of that, and I respect them for that.”