TU professor's field research sheds light on prehistoric Native American life

Assistant professor Katherine Sterner, anthropology students fill gaps in knowledge about Indigenous people in the Susquehanna River region

By Rebecca Kirkman on October 3, 2021

Neon orange flags stick out of a soybean field in the rolling hills surrounding the headwaters of Codorus Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna River in southern Pennsylvania.

Gesturing to the flagged locations, Towson University assistant professor Katherine Sterner explains that they mark the areas where her team of five undergraduate researchers found evidence of prehistoric Native American life during the first archeological field survey of the area.

Over five weeks during this past summer, Sterner and her students began to assemble the first cohesive picture of prehistoric life in the region through field study and lab work.

Previously, the only information came from the extensive private collection of Burnell Diehl, a local hobbyist who amassed hundreds of Native American arrowheads, tools and jewelry from the area—located 45 mintes north of TU—during the 1930s and donated them to York County Parks in 2003.

The current project began when Sterner—a second-year faculty member in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Criminal Justice who lives in nearby Loganville, Pennsylvania—stumbled upon Diehl’s collection while visiting the Nixon Park Nature Center with her family.

Like most private collections, the site where the artifacts were found was never reported to the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office and the site’s boundaries are unknown.

That’s where Sterner’s research comes in.

Not only is she looking for where Diehl collected the artifacts but also to characterize the geographic area through a field survey—the first step to better understanding what daily life was like at winter camps on the headwaters of the Susquehanna River.

“It’s a really underrepresented part of archeological research,” Sterner says, noting that most prior research has focused on the summer camps along the riverbanks. “But we also know historically, based on documentation from early European explorers, that Indigenous people took their winter camps into the headwaters.

“So that’s been an ongoing area of interest for me, to look at that interplay between village life and what life was like away from home.”

(Video: Henry Basta)

Similarly, looking at private collections offers researchers like Sterner an opportunity to fill gaps in knowledge.

“That's information that professionals haven't had access to and often we don't have locational information, or good locational information, on where it came from.”

Funded through the Office of Sponsored Programs and Research and the Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Inquiry, Sterner’s research exemplifies the true power of anthropology: offering a depth of perspective on the human experience. It’s why she believes every student should take at least one course in the discipline.

“Regardless of what you’re going to do for a career, an anthropology class is valuable because it’s going to give you that diversity of perspective and the opportunity to think about daily experiences and experiences of the past several million years,” Sterner says. “There’s no other discipline that does that.”

Putting Theory into Practice

On a 90-degree Wednesday in July, Sterner and two senior archeology students have returned to the field to look more closely at the areas where artifacts have been found throughout the five-week field survey. They dig 1.5-foot-wide holes at predetermined intervals and shake the soil through a wire screen to look for artifacts—a method called shovel testing.

What they’re looking for isn’t obvious to the untrained eye. Known in the industry as debitage, the small flakes of quartz they seek were removed when prehistoric settlers chipped away at larger stones to make tools. Archeologists distinguish debitage from pieces of rock by looking at shape and other marks that indicate it flaked off of a larger piece of rock after being struck.

“Quartz has a very blocky, crystalline structure, which can make it hard to chip,” Sterner says, holding up two quarter-sized pieces of quartz for comparison. “What we look for when we're determining if it was potentially culturally made, as opposed to something that might be hit by a plow, is a striking platform or termination—clear evidence of where it was struck by the person who was making it.”

If they find any artifacts, they bag them then record the depth, soil color and gravel content before filling the hole and moving on to the next.

For student researchers, shovel testing and identifying debitage is an opportunity to put what they learn in the classroom into practice.

“It was surreal going from the methods to the actual field work,” says Caitlyn Adams ’22, an anthropology major who received an undergraduate summer research grant for her work with Sterner. “I was digging in the ground, finding all these debitage pieces, and then I found something in the wall of the shovel test hole. I pulled it out, and it was a huge nail from maybe hundreds of years ago—not too far in the past and not what we were looking for, but it was still a really great feeling.”

Calliete Rose ’22, a biology and anthropology double major working in the field with Adams and Sterner, agrees.

“When you find something, it’s great,” they say. “Especially if you know it’s something. There’s a lot of ‘maybe-tage,’ which is when you find something and you’re like, ‘I think this is something,’ and then you go to the professor and you ask. If she says ‘yes,’ it’s like, ‘Yes!’”

The first phase of archeological excavation, shovel testing primarily allows researchers to define the boundaries of archeological sites and gather evidence to support further testing.

While physically demanding and less flashy than the full-scale excavations in later phases of archeological excavation, shovel testing offers students skills they can immediately use after graduation.

“Shovel testing is the bread and butter of what archeologists do in the mid-Atlantic,” Sterner says, explaining that work as a field technician in cultural resource management is a common entry-level job done to comply with federal and state preservation laws. “I wanted students getting experience actually doing that. It’s not as glamorous, and it’s not as fun because you don’t find as much stuff, but it’s a really valuable skill. And you can apply a lot of the same knowledge to those later phases of excavation.”

Opening Doors to Future Opportunities

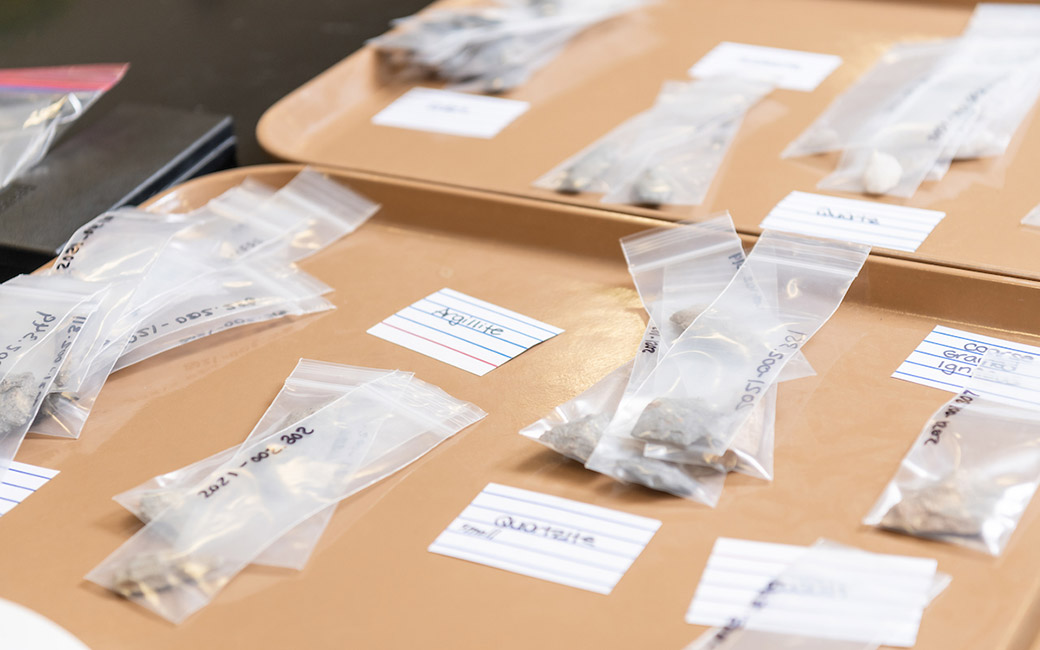

With field work concluded, research moves to a lab in the Liberal Arts building where Adams and Rose are cataloguing not only the artifacts they found during the field survey but also hundreds of prehistoric artifacts in Diehl’s personal collection, lent to the university by York County, and a collection on loan from the Natural History Society of Maryland.

“What we’re trying to get out of it is contextualizing all these artifacts that haven’t been contextualized yet,” explains Rose, as they record measurements on an iPad. “And inventorying them, because when I got them, we had no idea what was there.”

Combining lab and field work gives students two types of real-world experience. Rose hopes to take the skills they’ve learned into a professional career as a forensic anthropologist.

“There are so many different artifacts I’m looking at right now, and it’s [fascinating] to look at stuff that’s thousands of years old and see where people made changes to make it and the different decorations on it.”

While the team recorded eight positive shovel tests during the initial phase, they did not discover enough artifacts to justify further excavation of the area. Sterner credits this to several factors, including that the team didn’t have landowner permission to access the entire potential area Diehl may have collected from. Other issues include generations of erosion and plowing disturbing the topsoil as well as wetland mitigation along the banks of the creek, all of which disturb the soil and any artifacts it contains.

However, Sterner’s research helped identify the boundaries of the artifacts in Diehl’s collection as well as contributed to the gap in knowledge of the prehistory of southern York County.

GPS data from the site survey will be used to produce detailed maps of the survey results, allowing Sterner to make a rough interpretation of the settlement patterns.

She uses her research experiences as reference points in the classroom.

“Every project that I work on, I have examples that I can come back and use in class,” Sterner says. “If you’re not out there regularly experiencing this stuff, then you don’t have a touchstone to make it relevant to people.” This fall, Sterner is using the GPS point scatters from her research surrounding Codorus Creek to overlay the positive shovel tests with a topographic map, allowing students in her GIS in Anthropology class to see where the site boundaries fall on the landscape.

“Every place has a story to tell.”

And for Sterner’s undergraduate student team, it’s an experience that will shape their futures.

Adams looks forward to the opportunity to publish her research findings with Sterner. After changing her major twice, she says the experience has solidified her desire to work in anthropology.

“I love history, and I love artifacts, and I love just being out in the field and finding things,” Adams says. “So getting the experience to see what it’s like to be an archeologist is amazing."

Since signing on to conduct an independent study with Sterner, Rose has gotten additional work doing surveying and writing for Sandy Point Nature Center on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

“This experience, besides being a great opportunity that’s going to look amazing on my resume, has also opened a bunch of doors and networks to finding other opportunities,” Rose says. “This is the best thing I’ve ever chosen to do.”

Anthropology in Action

Learn more about how the project came to be and how it feels to discover an artifact in the videos below.

TU is leading enterprise research, discovering breakthroughs, building businesses and supporting communities.

Research for the public good.

Research & Discovery