Contribute Your Story / Become a Researcher

Help us make the site more nuanced, thorough, and equitable.

In 2014, an Internet search for “Asians in Baltimore” revealed extremely limited and

outdated information about the histories and contributions of the broad and ever-expanding

communities of APIMEDA (Asian Pacific Islander Middle Eastern Desi American) residents

whose customs, cultures, histories and creativity are integral to the fabric of the

greater Baltimore region. As greater Baltimore’s hub for uplifting and sharing Asian

stories, challenging anti-Asian hate, and promoting cross-cultural dialogue, the Asian

Arts & Culture Center (AA&CC) felt a need to become a resource for stories about the

region’s APIMEDA communities and embarked in 2015 on collecting them as best as we

possibly can, given our modest resources. (AA&CC is a self-support department of Towson

University which relies on charitable contributions of individuals, corporations,

foundations, and government agencies to keep our doors open and our programs running).

With a large and tenacious dose of passion to meet this challenge, we have created

this evolving archive developed from the ongoing work of staff, students, interns,

and community researchers and artists. A core of this content was produced as part

of our annual Asia North exhibition and festival, inaugurated in 2019 and co-produced

with the Central Baltimore Partnership and multiple community partners. As a celebration

of the arts and Asian culture that are defining characteristics of Baltimore’s Charles

North neighborhood (part of the Station North Arts & Entertainment District), Asia

North strengthened the AA&CC’s ability to document and share stories of greater Baltimore’s

APIMEDA communities. With Asia North’s focus on the Charles North neighborhood — the

site of Baltimore’s first unofficial Koreatown — we paid particular attention to greater

Baltimore’s Korean community.

We are fully aware of the glaring incompleteness and imbalances present on these pages.

Out of necessity and desire for openness and flexibility, this site is an evolving

one. We invite you to help us make it more nuanced, thorough, and equitable. Contact

AA&CC’s Director, Joanna Pecore at jpecore AT_TOWSON, with your ideas for contributing more stories. We’ll harness our ambition and do

our best to accommodate and include you!

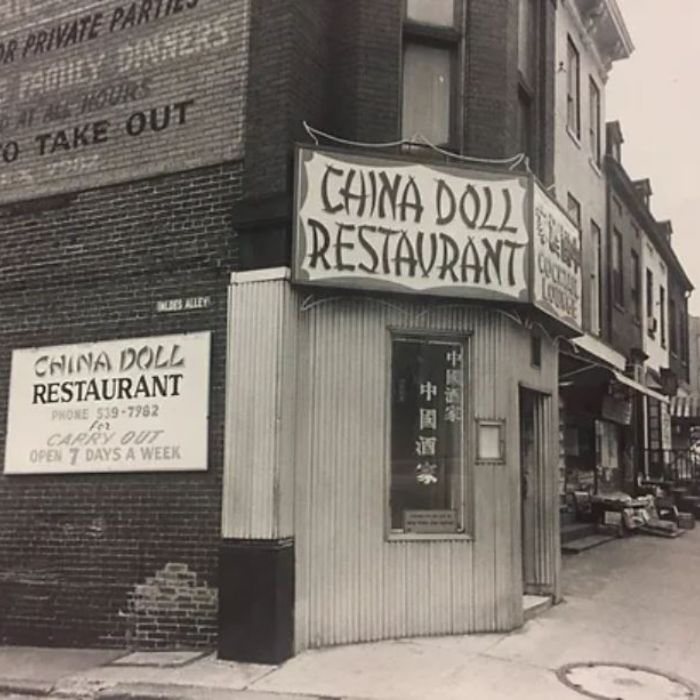

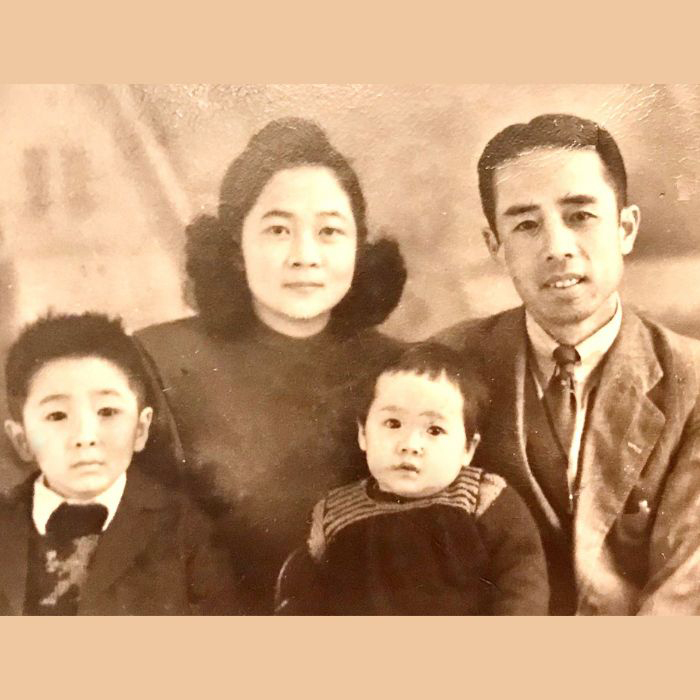

Did you know that Baltimore was once home to a small but mighty Chinatown? Traversing between “Past” and “Present,” this project traces out the contours of Baltimore’s historic Chinatown and examines its evolution and revitalization efforts today.

Learn More

Henry Chen, TU Professor Emeritus of Physics and an octogenarian, recounts his immigrant experience having lived in the U.S. for over 70 years.

Watch the Video on YouTube

Peter Chang, a finalist for the James Beard Award in the outstanding chef category, came to Baltimore in February 2023 to celebrate the reopening of NiHao, his restaurant in Canton.

Read the news article courtesy of The Baltimore Banner

Remembering a beloved matriarch and activist of Baltimore’s and Maryland’s Filipino-American community, who first picked up a paint brush at the age of 77.

Learn More

Retired Baltimore Sun foreign correspondent Gene Oishi's experience, growing up in a concentration camp in Arizona, informs his novel, "Fox Drum Bepop."

Read the article from January 2015 on Baltimore Magazine's website

Artist Rieko Chacey considers her immigrant experience as atypical in the Japanese American community and thinks of family as home.

Read her storyLearn more about Baltimore's first Koreatown, Soon He So, and Sookkyung Park as part of Korean American Community History.

Learn more about South Asian Community History.